The

Modern Chapel of the Wounded Jesus in Zagreb: An Architecture of Silence in the

Heart of the City

La moderna capilla de Jesús Herido en Zagreb. Una arquitectura del silencio en el corazón de la ciudad

Zorana Sokol-Gojnik

· University of Zagreb (Croatia) · zorana.sokol@arhitekt.hr

· https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2148-2243

Igor Gojnik

· Independent Scholar, Zagreb (Croatia) · igor.gojnik@siloueta.hr

· https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5338-6539

Recibido:

02/12/2025

Aceptado:

23/12/2025

Abstract

The Chapel

of the Wounded Christ in Zagreb, designed by Antun Urlich in 1936, represents a

rare example of modernist sacred architecture integrated within the city’s

historic core. Conceived as an architecture of silence, the chapel

transforms light, proportion, and material into carriers of spiritual meaning.

Embedded in the Foundation Building on Ban Jelacic Square, it contrasts the

noise of urban life with an inner atmosphere of contemplation. The research

interprets the chapel as both architectural and theological innovation, linking

Croatian modernism with wider European movements that sought new expressions of

the sacred through simplicity and clarity. Urlich’s minimal composition —stone,

glass, and light— creates a space where modern rationalism meets transcendence.

The chapel stands as a lasting dialogue between faith and modernity, proving

that silence and light can become the true language of sacred architecture

within the heart of the modern city.

Keywords

Antun

Urlich, Croatia, Modern Architecture, Sacred Architecture, Zagreb.

Resumen

La capilla del Cristo Herido de Zagreb, diseñada por Antun Urlich en 1936, representa un ejemplo excepcional de arquitectura sacra moderna integrada en el centro histórico de la ciudad. Concebida como una arquitectura del silencio, la capilla transforma la luz, la proporción y la materia en portadores de significado espiritual. Integrada en el Foundation Building, en la plaza Ban Jelacic, contrasta el bullicio de la vida urbana con una atmósfera interior de contemplación. La investigación interpreta la capilla como una innovación tanto arquitectónica como teológica, vinculando la modernidad croata con movimientos europeos más amplios que buscaban nuevas expresiones de lo sagrado a través de la simplicidad y la claridad. La composición minimalista de Urlich (piedra, vidrio y luz) crea un espacio donde el racionalismo moderno se encuentra con la trascendencia. La capilla se erige como un diálogo duradero entre la fe y la modernidad, demostrando que el silencio y la luz pueden convertirse en el verdadero lenguaje de la arquitectura sacra en el corazón de la ciudad moderna.

Palabras clave

Antun Urlich, arquitectura moderna, arquitectura sacra, Croacia, Zagreb.

Introduction

The Chapel

of the Wounded Christ in Zagreb is a unique example of modernist sacred architecture,

located in the historic centre of the city. Situated at Ilica 1, on the ground

floor of the Foundation Building next to Ban Jelacic Square, it is

simultaneously present and hidden. It forms part of the everyday rhythm of

urban life, yet remains a space of silence and contemplation.

The main

aim of this paper is to explore the architectural, spiritual, and urban

identity of the modern Chapel of the Wounded Christ, with particular emphasis

on the concept of silence, which in this chapel acquires a spatial and symbolic

dimension. The chapel is considered not merely as a building, but as a

spiritual phenomenon within the fabric of the modern city, where silence

—contrasting the external noise— becomes an architectural principle, and space

itself a symbol of divine presence.

The

research is based on the analysis of archival documents, [1] a review of existing literature on

the chapel, visual and spatial analysis of the site itself, and a comparative

study with other modernist sacred buildings in Croatia and Central Europe from

the 1930s (Fernández-Cobián 2007). Professional literature in the fields of

architectural history, the liturgical movement, and the theology of space

provides the framework within which the Chapel of the Wounded Christ is placed

in the broader context of European modernism.

Continuity of the Site

The origins

of the chapel date back to 1749, when the first chapel dedicated to the

Suffering Christ (Trpeci Isus) was built beside the Manduševac spring, with

the permission of Bishop Franjo Klobusic. Due to urban redevelopment and the

construction of the Foundation Hospital, the chapel was demolished in 1794, and

a new one was erected within the hospital complex that same year. Throughout

the 19th century, the chapel and hospital became inseparable parts of the

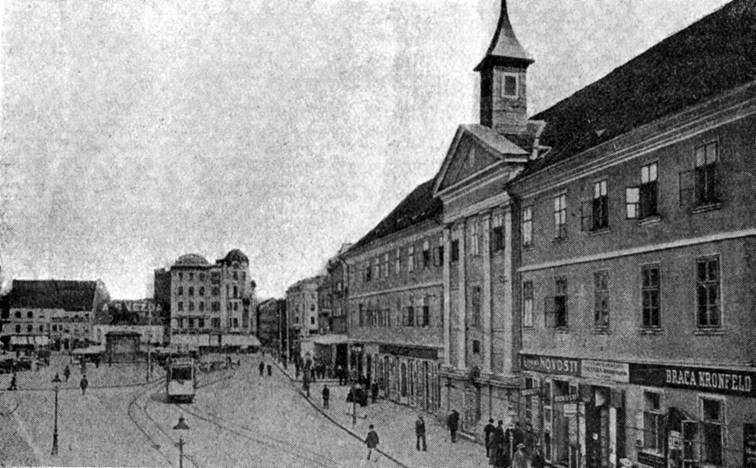

city’s identity, a meeting place of civic care and spiritual devotion (Fig.

01).

Fig. 01. The first

Chapel of the Suffering Christ on Ban Jelacic Square, Zagreb (Croatia), 1749;

demolished in 1794.

In 1803,

Bishop Maksimilijan Vrhovec entrusted the administration of the hospital and

chapel to the Order of the Brothers Hospitallers (Šegvic 1938). After the Order

left in 1918, the hospital was taken over by the City of Zagreb, but the

complex soon became inadequate for modern medical needs. Consequently, it was

decided to demolish the old hospital and build a new Foundation Block, a mixed

residential and commercial complex.

Through the

initiative of the chapel rector, Kerubin Šegvic, and the Foundation Board, it

was decided that a modern Chapel of the Suffering Christ would be incorporated

into the new building. Authors of residential building with the chapel were

Antun Urlich, Franjo Bahovec and Ivo Juranovic. According to archival records,

in 1934 architect Antun Urlich undertook the design of the new chapel. [2] The chapel was consecrated on

August 16, 1936, by decree of the Archiepiscopal Spiritual Court, thus

continuing the spiritual lineage from 1749 into the modern era. The

reconstruction of the chapel within the new structure represented both an

architectural reinterpretation and a theological affirmation, a transformation

of baroque devotion into a modernist architecture of silence.

The chapel,

although situated in the very heart of the city’s bustle, functions as an inner

counterpart to the external world. While traffic, commerce, and daily noise

flow outside its walls, within reigns a silence of light and sound. This

silence is not an absence, but a place of Presence, a space of contemplation

and meditation leading to an encounter with God (Fig. 02).

Fig. 02. Antun

Urlich, Chapel of the Wounded Jesus, Zagreb (Croatia), 1934-36; entrance facade

to the chapel.

Architect Urlich

did not design a monumental sanctuary, but rather an urban interior of

spirituality, an architecture that speaks the language of proportion, measure,

and light. In this sense, the Chapel of the Wounded Christ becomes a metaphor

of the modern city, a space that distills meaning from the surrounding noise.

It reflects what Vesna Mikic (2002) calls the «classicism of modernity», a

quiet discipline of form that transforms material into a space of spirit.

Zagreb in the 1930s: The City and the Rhythm of Modernism

During the

1930s, Zagreb underwent a period of intense modernization (Premerl 1990). The

city center, shaped in the 19th century within the spirit of historicism,

experienced a redefinition of its functions, façades, and spatial relations.

The 1930s

represent one of the most significant phases in the formation of modern Zagreb.

After the First World War, the city expanded rapidly: its population grew,

industry developed, and central urban areas demanded new spatial solutions. The

traditional urban matrix, dominated by monumental historicist buildings of the

late 19th century, increasingly failed to meet the functional requirements of

modern life. Within this context, modernism emerged as an architectural and

urban movement that found strong resonance in Zagreb (Radovic Mahecic 2007).

A central

role in shaping interwar Zagreb was played by the so-called Zagreb School of

Modern Architecture, a group of architects associated with Professor Drago

Ibler and the artistic collective Zemlja (Earth). Among its leading members

were Stjepan Planic, Drago Ibler, Drago Galic, Zlatko Neumann, Mladen

Kauzlaric, and others. Their work was characterized by faith in rationality,

functionality, and the social responsibility of architecture. In contrast to

Vienna Secession and late historicism, which had defined earlier decades,

modern architecture sought liberation from ornament and form shaped according

to the real needs of everyday life.

The

interwar period (Laslo 1982 and 1987) laid the foundations of 20th-century Croatian

architecture (Ivankovic 2016), during which Zagreb became a truly European

city, with achievements comparable to those of Vienna, Prague, or Budapest.

Modernism in Zagreb was both local and international: local in its sensitivity

to the urban and social context, and international in its engagement with

broader European currents.

One of the

key urban issues of the time was the so-called problem of closed city blocks.

While the city expanded eastward and southward, the 19th-century central

districts remained burdened by large enclosed blocks with internal courtyards.

These often housed inadequate auxiliary dwellings, lacking light, air, and

permeability between streets (Ivancevic 1983).

Architects

of the Zagreb School saw modernism as the solution to this problem. Instead of

closed blocks, they proposed semi-open and permeable ensembles with arcades,

inner courtyards, and green spaces—responding not only to functional needs but

also to the social idea of the city as a place of openness and communication.

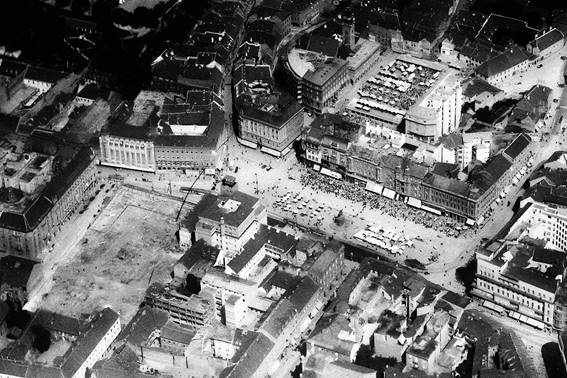

The most

complete example of modernist urbanism in Zagreb became the Foundation Block (Zakladni

blok), built between 1932 and 1937 on the site of the demolished Hospital

of Brothers Hospitallers. On this site unfolded the drama of demolishing

the old Hospital and its chapel and erecting a new modern complex (Bjažic

Klarin 2010). Today, this ensemble is a protected cultural monument and one of

the most significant examples of the International Style in Croatia (Fig.

03-04).

Fig. 03. The

site of the demolished Hospital of the Brothers of Charity, Zagreb (Croatia),

1932.

Fig. 04. The

location of the demolished hospital on a larger scale, 1932.

Following

the Hospital’s demolition in 1931, the city authorities announced, in 1929-30,

an open architectural competition for the parceling and design of this

prestigious location. The aim was to develop a urbanistic regulatory plan

defining the volume, height, and uniform appearance of the new block. The competition

attracted the leading architects of the period, including Drago Ibler, Stjepan

Planic, Josip Seissel, Josip Picman, Ernest Weissmann, and others.

The

subsequent debates in professional journals and daily newspapers revealed a

deep divide between conservative and modernist tendencies. Conservative critics

mocked the proposals as bare cubes and architectural fashions,

while modernists advocated for radical solutions — from megastructures spanning

Ilica Street to a proposed 42-meter-high tower (Bjažic Klarin 2010).

Ultimately,

a compromise solution was adopted: the regulatory plan from January 1930

combined elements from several competition entries. It prescribed the

construction of a unified block comprising nine buildings and a tower, with

strictly defined heights and façades to ensure visual coherence. Between 1932

and 1937, the Foundation Block was realized, bounded by Gajeva, Ilica,

Petriceva, and Bogoviceva Streets. This complex of mixed-use buildings is

regarded as the largest manifestation of the International Style in Zagreb’s

Lower Town (Donji grad).

The block

was built according to the principles of modern urbanism: clearly defined

volumes, rhythmic façades, glass shopfronts at street level, and rational

organization of residential and commercial spaces. Although conceived as a

unified whole, the final result was somewhat compromised: different investors

and architects had to comply with the prescribed parameters, leading to a

certain monotony, yet also to a coherent visual identity (Fig. 05).

Fig. 05. Antun

Urlich, Franjo Bahovec and Ivo Juranovic, New building built on the site of a demolished

hospital, Zagreb (Croatia), 1934-36; on the far right.

Ban Jelacic

Square thus became not only a traffic hub but also a symbolic center of the

city, a place of daily encounters, commerce, and the representation of modern

urban life.

In the

context of modernization, there arose a need for continuity of the spiritual

space that citizens had on that site since 1749, when the first Chapel of the

Suffering Jesus was built. The new Chapel of the Wounded Jesus (the name

changed from Suffering to Wounded) was realized within the Foundation Block, as

part of a residential building designed by architects Antun Ulrich, Franjo

Bahovec, and Ivo Juranovic. It was a response to this need, driven by the

strong desire of the citizens to restore a space deeply woven into their

spiritual life.

On the

initiative of Rector Kerubin Šegvic and with the approval of the Archiepiscopal

Spiritual Court, the new chapel was built in 1934. Its position as a sacred

space within a public building constituted a rare typological case in Croatian

interwar architecture. The chapel was conceived not as a hospital chapel, but

as a public sacred space: a place inviting meditation, pause, and

introspection, accessible to citizens, passers-by, and employees of the

Foundation.

Located

directly adjacent to the city’s busiest square, the chapel stands both at the

heart of urban life and apart from it. The sounds of the city —footsteps,

trams, voices— are subdued within its walls, creating a sense of spatial

isolation without physical distance. The chapel is entered directly from the

street, yet it is embedded within the structure of the block in such a way that

its zenithal opening brings natural light into the interior, animating the

architecture and giving it a spiritual dimension. Thus, the Chapel of the

Wounded Christ becomes an oasis of silence, light, and modernist architecture

in the very heart of the city.

The Modern Chapel of the Wounded Christ: The

Architecture of Silence

The chapel

was built within a residential building designed by Antun Ulrich, Franjo

Bahovec, and Ivo Juranovic, while the chapel itself was built according to the

design of architect Antun Ulrich, one of the prominent figures of Croatian

modernism in the interwar period. Ulrich belonged to the generation of

architects who introduced new spatial concepts, rationalism, and a disciplined

functional form to Zagreb, yet without renouncing the humanistic sensibility of

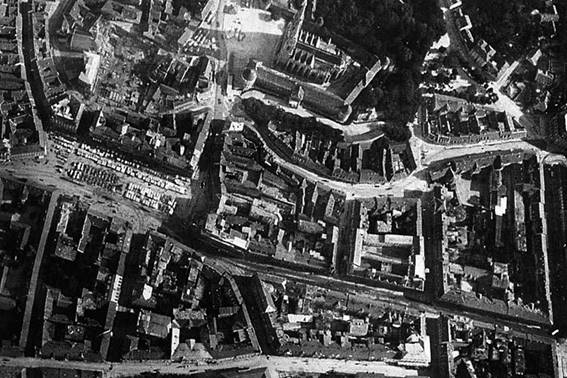

space (Mikic 2002) (Fig. 06).

Fig. 06. The

position of the Chapel of the Wounded Jesus on the site.

Urlich’s

modernist architecture, rooted in the Viennese architectural school, is based

on a disciplined, rational, and measured form derived from the classical

principles of proportion, order, and balance. His architecture aspires to

simplicity and constructive clarity. Instead of ornament, the main bearers of

expression are material and light; space is shaped as experience rather than

decoration (Fig. 07-08).

Fig. 07. Antun

Urlich, Chapel of the Wounded Jesus, Zagreb (Croatia), 1934-36; he entrance

facade (photo from the time of construction).

Fig. 08. The

entrance façade today.

In this

chapel, too, Urlich does not design a monumental church but rather a quiet

sanctuary within an urban building, following modernist principles of function

and restraint. On the façade, within the clean modernist grid of the Foundation

Building, a delicate white stone frame defines the boundary of the sacred

space. This frame is not decorative but precisely marks the threshold between

the sacred and the profane. The structural constraint of the building —the two

load-bearing columns— becomes a compositional motif of the façade.

In contrast

to the white frame, Urlich renders them in black, creating a strong visual

rhythm and counterpoint that leads the observer into the interior. Together,

the white frame and the black columns form a forecourt: a vestibule of silence,

a transitional zone between the noise of the city and the stillness of

devotion.

The

entrance façade itself is constructed of glass brick, arranged in six vertical

fields. In the center of the composition, between the two black columns, a

white stone cross is affixed to the glass surface: a point of repose and a

striking symbol of spiritual focus.

The entire

composition —white frame, black columns, white cross, and glass panels—

embodies Urlich’s modernist discipline: purity, proportion, order, and measure.

In this geometry of silence, material and light replace ornament, and

construction itself becomes a bearer of sacred meaning (Fig. 09).

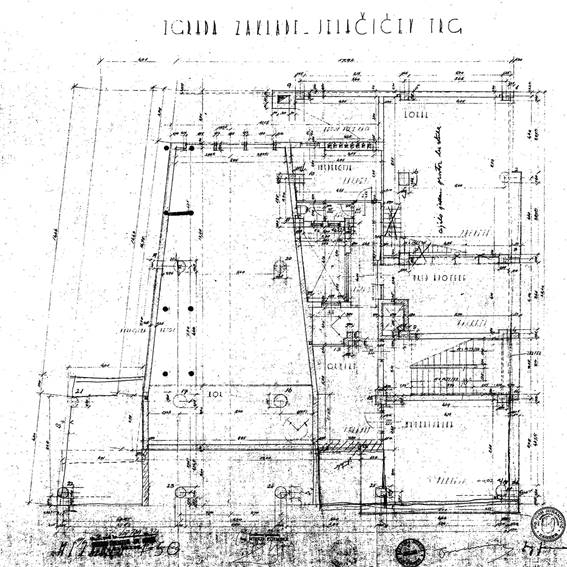

Fig. 09. Antun

Urlich, Chapel of the Wounded Jesus, Zagreb (Croatia), 1934-36; plan.

The glass

façade does not conceal but invites revelation of the interior. Glass, by its

nature, connects rather than separates; here, it admits light into the space.

The theme of light becomes the leitmotif of the architecture. Both the façade

and the rear wall of the presbytery define the spatial experience. The plan of

the chapel is trapezoidal, with two opposing glass walls through which light

enters, transformed through stained, glassimparting to the interior a sacred

atmosphere of peace and contemplation. The light of the chapel is soft,

discreet, and non-dramatic; it does not illuminate but rather invites the

discovery of divine Presence. In this way, glass and light become the primary

bearers of the sacred ambiance and spiritual experience. The space is shaped as

a materialization of silence, where the perception of sound and light turns

into a meditative encounter.

Crossing

the threshold into the chapel’s interior, the modernist principle continues

with quiet consistency. Behind the entrance glows the gentle illumination of

the stained glass window depicting Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane. The

image leads the visitor into the space dedicated to the Wounded Christ. On one

side stands Gethsemane, on the other Golgotha together forming a theological

unity of Christ’s suffering and redemption (Fig. 10-11).

Fig. 10. Antun

Urlich, Chapel of the Wounded Jesus, Zagreb (Croatia), 1934-36; view of the

presbytery.

Fig. 11. View

of the atrium.

Before the

visitor unfolds a total, unified space, where only two columns —again structural

necessities— create a subtle hierarchical distinction between the nave and the

presbytery. The whiteness of the entrance vestibule continues across the

ceiling into the darker interior, where the walls and floor are clad in dark

marble. The focus of perception is drawn toward the rear wall of the

presbytery, entirely filled with a stained-glass window depicting Christ on

Golgotha.

The stained

glass was the result of collaboration between architect Antun Urlich and

painter Marijan Trepše, with the support of famous artist Jozo Kljakovic. [3] Into the monochromatic

architectural palette, Trepše introduces a dramatic chromatic composition that

gradually fades toward the edges, blending into the dark marble walls.

At the luminous center stands the crucified Christ, beneath whose cross appear

Mary-Mother of Christ, Mary Magdalene and Mary of Clopas. This scene, suffused

with light and color, becomes an icon of transcendence, the focal point where

architecture, light, and faith converge.

The

presbytery space is elevated by only two steps above the nave. This slight

elevation reflects the liturgical movements of the early 20th century (Sokol

Gojnik 2017), which sought to affirm the communal dimension of the celebration

of faith by reducing the historical height difference between the presbytery

and the space of the congregation.

Archival

documents mention the clergy’s dissatisfaction with this modest elevation and

proposals to raise the altar further; however, these proposals were ultimately

rejected. Photographic documentation from the time of the original arrangement

has not been preserved, and the available drawings do not indicate the

architectural solution of the presbytery. Nevertheless, archival sources

mention an altar supported by columns, which was later adapted to the new

liturgy introduced by the Second Vatican Council, with the mensa

replaced by a smaller one. It is likely that the pre-conciliar altar (identical

to the present one) was positioned adjacent to the stained-glass window (NDS

3528/1972).

With its

minimalist design, the altar followed the formal stylistic vocabulary of the

architectural composition. The white mensa rested on five elegant black

columns. After the Second Vatican Council, the altar was moved closer to the

nave, the mensa was reduced in size, and on the black column identified in

archival documents as «the fifth altar column beneath the tabernacle», a

freestanding tabernacle was placed (NDS 3318/1960 and 3528/1972) (Fig. 12). [4]

Fig. 12. Antun

Urlich, Chapel of the Wounded Jesus, Zagreb (Croatia), 1934-36; detail of the

presbytery.

The floor

was executed in dark stone paving made of rasotica stone. Architect Ulrich

ceased work on the project on May 2, 1936, and documentation indicate that the

chapel remained unfinished. [5] The chapel was blessed on August

16, 1936.

Archival

data indicate that the area of the congregation and the presbytery were

originally separated by a stone communion rail, and that the chapel underwent

several phases of refurbishment during the 20th century. In 1950, wooden pews

and confessionals were installed, introducing a warm tactile contrast to the

predominant materials of stone and glass (NDS 3528/1972).

In 1969,

the statue of the Suffering Christ, preserved from earlier chapels, was placed

in the nave on a modest pedestal. [6] The walls feature discreet Stations

of the Cross.

The most

recent major renovation of the chapel began in 2024 and is currently ongoing.

The focus of the restoration is on providing an appropriate lighting solution

and addressing technical and functional deficiencies of the chapel, while

preserving all elements of the original design. The restoration is being

carried out by architects Igor Gojnik and Zorana Sokol Gojnik.

The Chapel of the Wounded Christ in the European

Context

The Chapel

of the Wounded Christ in Zagreb, though spatially modest and discreetly

situated on the ground floor of an urban building, raises questions that

transcend its local setting. It belongs to the broader European modernist

movement which, in the first half of the 20th century, sought a new expression

of the sacred: one liberated from historical styles and material rhetoric

(Premerl 1994). This search reflects a desire to express the sacred not through

monumentality, but through spatial clarity, proportion, and light as the

primary carriers of meaning. Thus, contemporary sacred space is defined through

light, matter, emptiness and silence, not through figurative or decorative

programs (Gonçalves 2017).

What Ulrich’s

chapel shares with European modernism is the conviction that sacred

architecture is not constructed through decoration or imagery, but through

space itself. Across Europe, between the two World Wars, a similar conceptual

tone emerged: architecture was understood less as a representation of Church

doctrine through rich iconography, and more as a medium of experience, a space

enabling contemplation, silence, and communion. Through this, the chapel

becomes a space of mission, proclamation, encounter, communion and sacraments,

and not just a liturgical object (Longhi 2013).

In this

lies the European contemporaneity of Ulrich’s work: in the belief that the

silence created by architecture can itself be a modernist category. Here,

silence is not an absence, but a spatial condition, an architectural outcome of

proportion and light. In this sense, the Chapel of the Wounded Christ resonates

with the same spiritual horizon that gave rise to the churches of Schwarz,

Böhm, Perret, and Michelucci, spaces in which the encounter with God is

mediated through space itself.

The central

idea of the modernist epoch is simplicity as an expression of depth. An

architect does not just design a building, but a space of experience. Ulrich’s

chapel exemplifies this principle: its structure is openly visible, detailing

is reduced to a minimum, and everything not serving function or light is

omitted. This reduction is not a negation, but a means of reaching faith

through the honesty of structure, architecture, and form. The Chapel of the

Wounded Christ also represents a rarity within the European typology: an

embedded chapel situated within a secular urban block at the very heart of the

city. Most modernist churches were constructed on the urban peripheries, within

new residential developments seeking their own spiritual infrastructure.

Ulrich’s space, by contrast, emerged within the densest and oldest fabric of

the city: on the ground floor of a public Foundation Building, surrounded by

shops, traffic, and the rhythm of everyday life. This location transforms the

chapel into an urban experiment. Ulrich thereby realizes what might be

described as a spiritual heart of the city, an experience born not from

withdrawal from the world, but from encounter with it.

This idea

of silence at the center of movement reverberates through European architecture

of the later twentieth century. From Fisac to Zumthor (Delgado 2007,

Vukoszávlyev 2013), numerous architects continued this line of thought,

conceiving space as an atmosphere of divine presence. Ulrich’s chapel may thus

be read as a precursor, an example anticipating the phenomenological

understanding of space: architecture not as an object, but as an experience of

light, touch, and proportion. Within its serene geometry and material

simplicity, one perceives the idea that the deepest modernity is that which

allows for silence.

The Chapel

of the Wounded Christ is not merely a Croatian episode of modernism, but its

quiet European echo. It is an example of how the modern spirit responded to the

enduring question of creating a space for encounter with God.

Conclusion

The Chapel

of the Wounded Christ in Zagreb synthesizes the fundamental tensions of the

modern epoch: between tradition and innovation, between the rhythm of the city

and inner contemplation, between the visible and the spiritual.

From the

first chapel by Manduševac in 1749, through the Baroque sanctuary of the

Hospital of Brothers Hospitallers, to Ulrich’s modern interpretation in 1936,

the same theme has been continuously reiterated within the same urban locus:

the city’s enduring need for a space of encounter with God. This continuous

sacred presence within the changing urban fabric reveals the interdependence of

spirituality and the city: as the city transforms, so too does the architectural

expression of faith, yet the need for presence remains constant.

In Antun

Ulrich’s modernist reinterpretation, the chapel becomes an architectural

expression of this relationship: a sacred center embedded within a secular

environment. Its spatial reduction, absence of ornament, and pronounced

presence of light are not merely aesthetic decisions, but gestures arising from

an attempt to comprehend the spiritual aspirations of the modern human being.

Ulrich thus

aligns with the broader European modernist discourse that recognized in light

the architectural key to the expressiveness of sacred space. The

distinctiveness of the Zagreb chapel lies in its urban context. Situated in the

very heart of the city, within the Foundation Building, it is not a secluded monastic

enclosure but a sanctuary amid everyday life. This relationship to the city

makes it one of the rare examples of modern architecture that does not seek

distance from life, but its transformation.

In a wider European

perspective, Ulrich’s work shares the intellectual premises of those architects

who, in the first half of the twentieth century, redefined the notion of sacred

space. As in the works of Schwarz, Böhm, or Perret, light here becomes the

primary formal and symbolic element. Yet, unlike the monumental compositions of

European churches, Ulrich creates a miniature of sacred space, an architecture

of intimate encounter (Sokol Gojnik 2017).

The Chapel

of the Wounded Christ thus represents an authentic Croatian contribution to

European modernism (Sokol-Gojnik et al 2019), not as a derivative of greater

models, but as an autonomous expression within the same intellectual horizon.

At a time when the city was expanding outward, Ulrich created a space that turned

inward: a space of light, proportion, and silence, where modern architecture

attains its spiritual fullness.

Bibliography

Bjažic Klarin, Tamara. 2010. «Zakladni blok u Zagrebu: Urbanisticke i arhitektonske odlike». Prostor 2(40): 322–335.

Delgado Orusco, Eduardo. 2007. «Las iglesias de Miguel Fisac». Actas de Arquitectura Religiosa Contemporánea 1: 130-161. https://doi.org/10.17979/aarc.2007.1.0.5021

Fernández-Cobián,

Esteban. 2007. «Arquitectura religiosa contemporánea. El estado de la

cuestión». Actas de Arquitectura Religiosa Contemporánea 1: 8–37. https://doi.org/10.17979/aarc.2007.1.0.5016

Gonçalves, José Fernando. 2017. «Sacred Spaces. Meaning, Design, Construction». Actas de Arquitectura Religiosa Contemporánea 5: 220–229. https://doi.org/10.17979/aarc.2017.5.0.5153

Ivancevic,

Radovan. 1983. «Blok

zakladne bolnice u Zagrebu – spomenik moderne arhitekture». Covjek i prostor

363(6): 30–34.

Ivankovic,

Vedran. 2016. Le Corbusier i hrvatska škola arhitekture. Zagreb:

Europapress holding (EPH).

Laslo,

Aleksandar. 1982. «Zagreb, Arhitektonski vodic I». Covjek i prostor

354(9): 15–19.

Laslo,

Aleksandar. 1987. «Zagrebacka arhitektura 30-tih. Vodic». Arhitektura

40(1-4): 97–112.

Longhi, Andrea. 2013. «Construir iglesias más allá de la arquitectura religiosa. Evangelización y arquitectura». Actas de Arquitectura Religiosa Contemporánea 3: 1–25. https://doi.org/10.17979/aarc.2013.3.0.5078

Mikic,

Vesna. 2002. Arhitekt Antun Ulrich – klasicnost moderne. Zagreb: Naklada

Jurcic.

Premerl, Tomislav. 1990. Hrvatska moderna arhitektura izmedu dva rata: Nova tradicija. Zagreb: Matica Hrvatska.

Premerl, Tomislav. 1994. «Crkveno graditeljstvo dvadesetog stoljeca». In Sveti trag: devetsto godina umjetnosti Zagrebacke nadbiskupije: 1094-1994, catalog of exibition, edited by Tugomir Luksic, Muzej Mimara & Izlozba Sveti Trag, 156-169. Zagreb: MGC/Muzej Mimara.

Radovic-Mahecic. 2007. Moderna arhitektura u Hrvatskoj 1930-tih. Zagreb: Školska knjiga.

Sokol-Gojnik,

Zorana. 2017. Sakralna arhitektura Zagreba u 20. stoljecu: Katolicke

liturgijske gradevine. Zagreb: UPI-2M PLUS.

Sokol-Gojnik, Zorana, Igor Gojnik and Marija Banic. 2019. «Interventions in Heritage Sacred Architecture after the Second Vatican Council in Croatia». Actas de Arquitectura Religiosa Contemporánea 6: 114–129. https://doi.org/10.17979/aarc.2019.6.0.6232

Šegvic,

Kerubin. 1938. Kratka povijest crkve Ranjenog Isusa na Jelacicevom trgu:

1749-1919. Zagreb:

Hrvatske Straže.

Vukoszávlyev, Zorán. 2013. «Obvious or Hidden. Evolution of Forms Used for Temporary or Permanent Small Sacral Spaces at the Turn of the Millennium». Actas de Arquitectura Religiosa Contemporánea 3: 64–71. https://doi.org/10.17979/aarc.2013.3.0.5086

Source of images

Fig. 01-05,

07-08, 10-12. Author’s archive.

Fig. 06.

State Archives in Zagreb, Collection of Construction Plans, microfilm, Hospital

130.

Fig. 09.

State Archives in Zagreb, Collection of Construction Plans, microfilm, Hospital

459.

Notes

[1] Documentation of the Hospital and the Church of the Wounded Jesus following archives: Nadbiskupijski arhiv, Nadbiskupski duhovni stol (NDS), Zagreb; Državni arhiv u Zagrebu, Gradsko poglavarstvo, Zagreb. Graðevinski odjel, Bolnica, Ilica 1.

[2] Sabiranje milodara za kapelu

Trpeæeg Isusa. Architect

Antun Ulrich is mentioned as a member of the Construction committee (NDS

1591/1937).

[3] Archival documents mention the priests’

dissatisfaction with the height of the presbytery, and in 1950 it was suggested

that the altar be raised, but that proposal was rejected (NDS 3528/1972).

[4] In archival documents it says: «The current

altar in the church does not meet the needs of the liturgy. The mensa is too

low, and the supporting block covers the lower part of the composition on the

glass depicting the Crucifixion. The adaptation project proposes

constructing a base that follows the ground plan of the altar and expands

towards the nave as far as the distance between the steps allows. The existing

mensa is supported by four round, turned columns of the same stone and a fifth,

central column, which supports the mensa beneath the tabernacle. The existing

tabernacle has been retained» (NDS 3528/1972, document no. 83/66, from July,

17th, 1966). The topic is the altar versus popoli. The letter states

that the altar remains the same, but is being moved, and the tabernacle is

being fixed to a separate pillar.

[5] Ulrich declares that he is withdrawing from «the

Community formed for the purpose of carrying out the renovation of the Chapel

of the Suffering Jesus on Jelasicev trg, and no longer has any obligations

towards you, the architect Bahovac, or the Committee for the construction of

this chapel. You will complete all the work required for its completion

yourself, as you have done so far. Consequently, I have no claims whatsoever

against you or the Committee for the construction of the Chapel of the

Suffering Jesus regarding the architectural work for the construction of this

chapel» (NDS 1591/1937).

[6] In 1941, at the initiative of Kerubin Šegvic,

a side altar of the Wounded Jesus was placed in the chapel, which also served

as the tomb of God during Holy Week. This arrangement was later abandoned, and

the historical statue of the Wounded Jesus was subsequently brought to the

chapel.