Worldwide, chronic non-communicable diseases are the main cause of death and disability (). Cancer ranks as the third leading cause of death in Mexico, with an estimated 195,500 new cases of different cancer types diagnosed annually (; ). The management of cancer requires the collaboration of multiple providers, care settings, and specialized health professionals—including physicians, nurses, nutritionists, psychologists, and palliative care teams, among others—who must work together to achieve a common goal: optimizing and coordinating patient care (). The availability of highly qualified professionals who can competently manage the clinical and emotional challenges associated with the disease is of critical importance ().

Essential in patient-centered care, clinical staff’s professionalization involves the acquisition of updated technical knowledge together with the development of communicative, humanistic, empathetic, and evidence-based skills (; ). Along the cancer care continuum, which comprises addressing in a comprehensive and participatory manner the various aspects of prevention, treatment, early detection of complications, survivorship, and end of life care, nurses play a fundamental role (; ). Training and competencies programs are recommended beyond basic nursing education (; ; ). Within oncology nursing, the refinement of communication skills in the context of palliative care is recognized as essential, alongside the strengthening of psychosocial and technical competencies (). Moreover, nurse-administered psycho-oncological education has been shown to reduce patient’s psychological distress (). Among the many opportunities for nurses to optimize patient care, since oncology patients develop different levels of distress, positive caring behaviors that reinforce the patient-staff relationship are also relevant (; ).

Oncology training programs have proven effective at improving nurse's aptitudes in various fields, from a wide range of performance and confidence skills to specific counseling and communication abilities (; ; ). However, studies that describe the impact of educational interventions over oncological knowledge on cancer related topics are limited (). Existing evidence, predominantly from quasi-experimental studies, suggests that educational interventions effectively improve nurse’s knowledge in certain oncology fields. One study found that a theory-based program can enhance nurse's knowledge and attitudes regarding cancer pain management (). Other authors showed that a palliative care educational program improved nurse´s knowledge and behaviors on the subject (). Additionally, other quasi-experimental studies have demonstrated a positive impact of training interventions in various areas, including improved nurse’s work attitudes and teamwork in the workplace, enhanced care for children with traumatic brain injury, and increased nursing presence in the post-operative setting (; ; ). In contrast, other studies have reported suboptimal nursing evidence-based general oncology practice implementation and overall inadequate palliative care knowledge, highlighting the need for further interventions (; ).

Given the need to broaden the body of evidence on the effect of educational interventions over clinical staff’s knowledge, on the otherwise scarcely documented oncological field, this study’s main objective was to assess the impact of a nursing training program on nurse’s knowledge on 2 variables: general oncology and palliative care, as part of the initial phases of implementation of a Comprehensive Oncology Center’s care model in a private hospital in Puebla, Mexico. As a secondary goal, an assessment of participant’s caring behaviors perception was included. Consequently, compared to pre-test scores, a score improvement over knowledge variables after the intervention, was expected.

Method

Participants

A total of 12 voluntary participants from a private hospital’s nursing staff located in Puebla Mexico, completed all questionnaires and were assessed before and after the intervention. The inclusion criteria comprised voluntary enrollment of nursing staff employed at the hospital during the evaluation period, a minimum of 90% attendance to theoretical sessions, and the availability of complete pre- and post-course evaluation data.

Amongst participants, mean age was 28.5 ± 3.3 years, 10 were women and 2 men, with ages ranging from 25 to 36 years. Most of the participating nursing staff were single, had no children, and had at least 4-6 years of experience. More than half of the staff had no prior training in general oncology or palliative care (Table 1).

Instruments

Previously identified as two key educational needs, in the context of a wide-ranging and complex cancer-care continuum: the specific case of end-of-life and general knowledge in oncology were assessed through the following ():

General oncology knowledge questionnaire

A 20-item multiple-choice general oncology knowledge questionnaire derived from the program’s contents was developed by the hospital’s charge nurses, which were responsible for the course’s theoretical implementation, ad hoc for this study. Each correct answer summed 5 points and 100 was the maximum score. The following are examples of the questions included: a) The mechanism of action of alkylating antineoplastics is; b) To counteract the side effects of paclitaxel, would you administer? The questionnaire was answered by participants before and after the training course.

Palliative care knowledge test

An expert validated questionnaire in Spanish was employed to assess general nurse’s knowledge across various palliative care domains (). The latter survey instrument was grounded in a previous 25-item adaptation by Medina Zarco et al., validated in Mexican healthcare professionals (). The instrument’s reliability was initially determined by Nakazawa et al., with a global 0.88 intraclass correlation and 0.81 Kuder Richardson formula result in internal consistency (). The modified version by Ordoñez Molero et al. used in this study comprised a total of 30 items: 7 on general knowledge, 5 on bioethics, respect, and communication towards the patient, 5 questions on spirituality, 7 questions on palliative care symptoms, and 6 involved pharmacology general knowledge. The score in each subdomain is added (correct = 1 point, incorrect = 0 points) yielding a maximum of 30 points. The following are examples of questions included: a) Palliative care, is only applicable to cancer patients?; c) Is palliative care’s main objective to ensure the quality of life of the patient, family, and caregiver? ().

Caring behaviors perception scale

This validated instrument, which has demonstrated strong reliability with a reported global Cronbach's alpha of 0.97 and a 90.9% variance in a 4-factor analysis, was used at baseline to assess nursing staff's caring behaviors perception (). This evaluation consists of 63 items with the following LIKERT-scale response options: 1 = little importance, 2 = relatively important, 3 = moderately important, 4 = important and 5 = very important. After adding all points, the minimum score is 63 and the maximum 315. The higher the score, the better the perception of caring behavior provided by nurses. This scale integrates seven subscales: 1) humanism/faith-hope/sensitivity (items 1 to 16); 2) help/trust (items 17 to 27); 3) expression of positive/negative feelings (items 28 to 31); 4) Training/education (items 32 to 39); 5) support care/protection/environment (items 40 to 51); 6) assistance with human needs (items 52 to 60); and 7) existential/phenomenological/spiritual forces (items 61 to 63). Some examples of the questions included are: a) I treat the patient as an individual; and b) I try to see things from the patient's point of view.

Procedure

This was a prospective pilot study, with a quasi-experimental pre-test/post-test design, conducted during the initial phases of a Comprehensive Oncology Center (COC) implementation, located in the facilities of a private care hospital in Puebla, Mexico. A comprehensive oncology care model (COCM) was designed during COC’s initial phases of implementation. Prior to the COC’s start of operations, the educational component of the model included a clinical staff training program, that comprised an oncology nursing 6-month training course, which began in January and ended in June 2024. Initially, thirteen nurses volunteered for the training course. At the conclusion of the program, only one participant failed to complete all pre- and post-program evaluations.

Comprehensive oncology care model

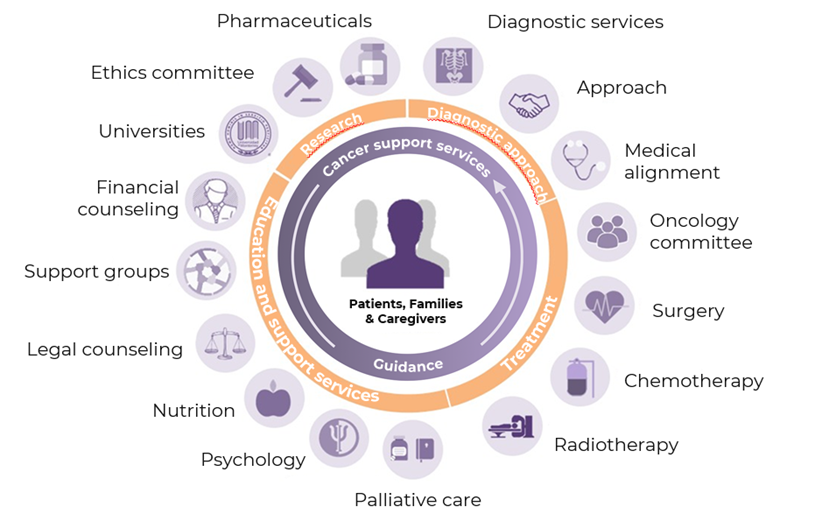

The COCM focuses on providing healthcare services in a coordinated, comprehensive, efficient, humanized, and safe manner. During the patient's admission and discharge process, the goal is to ensure high-quality pharmacological and non-pharmacological care. The model revolves around cancer patients, their families, and/or caregivers and comprises four main pillars a) diagnostic approach, b) care and treatment, c) patient and caregiver support, and d) education and research (Figure 1). The care directed to COC’s patients has a humanistic approach led by a multidisciplinary health team that involves oncology, algology, nutrition, psychology, rehabilitation, spiritual care, and palliative care experts, along with a skilled nursing service.

COCM’s educational component

The educational plan aimed at COC’s possible collaborators involved a beforehand detection of the private hospital’s nursing staff’s professional and training needs. After the latter process, collaborators were encouraged to participate in the COCM’s professionalization program, which involved, among other possibilities, an oncology nursing training program. The program emphasized the patients’ and their families’ emotional and spiritual aspects of care and included various topics on oncology nursing evidence-based practice (Table 2). The primary objective was to strengthen the knowledge and competencies of participating nursing professionals in delivering specialized care to cancer patients, utilizing workshops and the nursing care process as tools for care planning (; ).

The hospital’s nursing head office was responsible for the course’s advertisement and supervision. Informative leaflets and posters were distributed to all unit collaborators and staff, encouraging individuals to enroll in the program. The course had a capacity of 16 participants, allowing for personalized attention and intensive learning. The 180-hour training course consisted of a theoretical component conducted from January 23 to May 23, 2024, and a practical component comprising 70 hours, held from May 28 to June 27, 2024. Hearings were divided into two 5-hour sessions per week. Oncology and palliative knowledge questionnaires were answered during the course’s first two weeks and at a 1-2-week time-lapse after its conclusion.

The study was conducted in compliance with the bioethical principles of autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice, in accordance with the Nursing Ethics Code, the Mexican General Health Law, and the NOM-012-SSA3-2012. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, ensuring their voluntary participation and data confidentiality. Participant’s autonomy was respected, and any harm was avoided, maximizing the benefits of the study.

Data analysis

Categorical variables were described with frequencies and proportions, while numerical variables through means, standard deviations, medians, and interquartile ranges (IQR), where appropriate. For the evaluation of the oncology and palliative care knowledge variables, before and after the nursing training program, each questionnaire’s total and/or subdomain scores in the first versus the second evaluation were analyzed with the Wilcoxon signed-rank text. An r statistic (r = Z/√N, were N = the number of observations) was calculated to determine the effect size, and Cohen’s guidelines were used for its interpretation (; ; ). The information was analyzed with SPSS statistical package for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL version 20).

Results

According to the study’s main objective, differences between pre- and post-test scores were analyzed with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Table 3 shows that in the oncology general knowledge evaluation, when comparing before vs after-training results, a significant total-score improvement was found. Likewise, in the palliative care scale, a significant improvement was observed in participants' scores, both in the total score and across the general knowledge, symptom management, and pharmacology domains. Additionally, as a complement to statistically relevant results, a medium-effect size was observed in the general oncology knowledge questionnaire results (r=-.449). In the palliative care scale results, a large effect size was observed in both the total score and the general knowledge subdomains (r=-.569 and r=.554, respectively), and a medium-size effect in the symptoms and pharmacology subdomains (r=-.406 and r=-.451, respectively).

| Variable | Before Score (IQR) | After Score (IQR) | Z | r value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oncology general knowledge | 35.0 (30.0-40.0) | 55.0 (44.2-63.0) | -2.200* | -.449 |

| Palliative Care | ||||

| General Knowledge | 5.0 (4.0-5.7) | 7.0 (6.0-7.0) | -2.716** | -.554 |

| Bioethics, respect, and communication towards the patient | 4.5 (4.0-5.0) | 5.0 (4.2-5.0) | -1.027 | -.209 |

| Spirituality | 4.5 (4.0-5.0) | 5.0 (5.0-5.0) | -1.933 | -.394 |

| Symptoms | 3.0 (2.0-4.0) | 4.5 (3.0-6.7) | -1.992* | -.406 |

| Pharmacology | 3.5 (2.2-4.0) | 4.0 (4.0-6.0) | -2.214* | --.451 |

| Total score | 20.0 (18.0-22.0) | 24.5 (22.5-28.7) | -2.791** | -.569 |

A description of participant’s caring behaviors was included in Table 4 as a secondary goal. Nurses’ total score in the caring behaviors scale at baseline was 272/315 points. Expression of positive/negative feelings and forces (existential, phenomenological, and spiritual) were ranked within the highest medians from amongst the caring behaviors subdomains.

Discussion

An innovative comprehensive oncology care model, described during a COC’s pre-operational phase, integrates a fundamental component in patient quality care: clinical staff’s professionalization through educational programs aimed at health care providers. Through a pilot exercise that involved an oncology nursing training program, a positive impact in participant’s oncology and palliative care knowledge was observed. Positive caring behaviors were also noticed amongst participants.

As a main objective, an assessment of the impact of an educational oncology program on nurses’ knowledge over general oncology and palliative care scores, the latter representing an essential component of the cancer care journey, was performed. Authors of a Swedish pre-test post-test study found that a well-structured, theory-based intervention, despite being brief (a 2-hour workshop), significantly improved nurses’ knowledge of cancer pain management compared to a control group. The intervention was based on concepts such as participants’ behavioral and normative beliefs, perceived social pressure to perform, and self-efficacy (). In this study, three separate measurements were conducted: at baseline, 4 weeks, and 12 weeks after the intervention, with resulting knowledge scores of 25.7, 27.6, and 26.5 out of a maximum of 28 points, respectively. Similarly, Harden and collaborators reported that a one-month palliative care training program conducted in the United States (US) significantly improved oncology nurses’ knowledge in this field (). Other studies have also demonstrated the positive impact of nursing educational interventions on staff knowledge across various healthcare areas (; ). However, to our knowledge, no experimental studies evaluating interventions aimed at improving oncology-related knowledge or skills among nursing staff have been identified in Latin America.

At baseline and as a secondary goal, future COC’s nursing staff showed high levels of positive caring behaviors. Reynaga-Ornelas et al., in a group of Mexican nurses from different hospital settings, also reported positive perceptions on the same scale, but especially in the assistance to human needs subdomain (). Furthermore, another Korean study focused on the degree of oncology nurses’ caring behaviors and found them related to the further development of holistic nursing care, through an enhancement in their professional quality of life and education (). However, authors from the latter study utilized a different instrument for caring behavior evaluation. In the present study, expression of positive/negative feelings and forces (existential, phenomenological, and spiritual) were the highest caring behaviors amongst participants. Other authors, also utilizing a different instrument, have reported other predominant caring behaviors such as "treating patients’ information confidentially", "treating the patient as an individual", and "demonstrating professional knowledge and skill" as the most important caring behaviors amongst mostly the internal medicine or surgical departments nursing staff ().

Regarding participants' sociodemographic characteristics, Gustafsson & Borglin’s study on cancer pain intervention reported an overrepresentation of the female gender, as all participants were women (). According to the authors, more than 90% of registered nurses in Sweden are female. While similar proportions are observed in countries such as the US and Mexico, recent trends indicate a growing number of male nurses (; ). Evidence suggests that both genders achieve equally optimal performance in nursing practice. Furthermore, patients’ preferences are primarily influenced by nurse’s individual performance and other professional attributes (; ).

Another characteristic from Gustafsson and Borglin’s study participants was that nurses had <5 years of experience. Although most nurses that participated in the present study were more experienced, no impact over the intervention’s efficacy on knowledge scores was observed in neither study. Moreover, authors in Argentina also reported a low percentage (12%) of exposure to information related to palliative care in nursing and that only 18% of the participants had appropriate knowledge on the topic (). Cross-sectionally, a study in Mexico also found a low percentage (35%) of correct answers using the same Palliative Care Knowledge scale (). In the present study, almost half of participants had no previous history of either oncology or palliative care training, and although low at baseline, nurse’s scores improved after the oncology nursing program. It must be recognized that hypotheses that concern sociodemographic differences that influence nurse’s knowledge or performance must be properly addressed in future studies.

Limitations in the present study must be recognized. A small sample remains a fact that renders this study’s results unrepresentative for larger populations and other clinical settings. The study’s design and its pilot component only allow observations of one phenomenon and the presence of biases cannot be ruled out, especially in the context of a self-developed instrument to evaluate staff’s knowledge, which must be further and adequately validated. However, this first experience can be useful in the identification of theoretical contents that need to be considered and improved for future purposes. Moreover, when comparing results to literature, given that other authors employed different instruments to evaluate palliative care knowledge among nursing staff across diverse workplace settings, inter-population comparisons remain challenging. Lastly, palliative care and oncology general knowledge constitute roughly a small part of a broader oncology nursing care framework in which psycho-oncological education, communication, and specific technical nursing skills, among others, can play a much larger and necessary role. Interventions that effectively increase evidence-based practice among nurses and that are further confirmed to be effective on patient outcomes are deemed essential in quality health care ().

The advantages of the present study lie in the fact that the information obtained through observation during the implementation of an oncology care model serves as a valuable source of knowledge, offering an opportunity to generate future hypotheses. Although only a small part of the COCM’s implementation experience was described, a focus on its educational component is fundamental in the creation of innovative knowledge that can continually improve cancer patient care. Moreover, these results suggest that, despite the fact of a limited sample, an educational intervention had a positive and significant impact on nurse’s knowledge. Based on these findings, further research with larger samples could not only validate the results across different contexts but also contribute to the development of more effective educational strategies. It is essential that in the future, besides enhancing nursing intervention evaluations with well validated instruments, that the transfer of knowledge to everyday practice can also be evidenced. Oncology care models that incorporate educational programs for healthcare providers should strengthen evaluation processes to identify the most effective teaching methods and curriculum content in this field. These strategies could contribute to both, the strengthening of nursing staff’s professional performance and the improvement of patient centered quality of care. Nonetheless, to enhance the robustness of findings, the next step should consider randomization between intensive vs habitual educational interventions.

These results suggest that the oncology care model’s educational intervention has been effective at improving health care provider’s oncology and palliative care knowledge. The experiences and observations made during this phase of the COCM’s implementation process can lay the foundations and serve as experience for upcoming educational interventions on a grander scale. In the future, new hypotheses can arise to nurture forthcoming research on this scarcely documented topic.

References

1

ABU-BAKER, Nesrin N.; ABUALRUB, Salwa; OBEIDAT, Rana F.; & ASSMAIRAN, Kholoud (2021). Evidence-based practice beliefs and implementations: A cross-sectional study among undergraduate nursing students. BMC Nursing, 20, Article 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-020-00522-x

2

ALDACO SARVIDE, Fernando (2009). Los retos de la oncología en México: El futuro ya es pasado. Gaceta Mexicana de Oncología, 8(4), 133-134. https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-gaceta-mexicana-oncologia-305-articulo-los-retos-oncologia-mexico-el-X1665920109501354

3

AL-HASNAWI, Ameer Aqeel; KANIM, Murtadha; & ALJEBORY, Adea (2023). Relationship between nurses’ performance and their demographic characteristics. Journal Port Science Research, 6(1), 11-15. https://doi.org/10.36371/port.2023.1.3

4

ALIKARI, Victoria; GEROGIANNI, Georgia; FRADELOS, Evangelos C.; KELESI, Martha; KABA, Evridiki; & ZUGA, Sofia (2022). Perceptions of caring behaviors among patients and nurses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), Article 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH20010396

5

ALJURF, Mahmoud; MAJHAIL, Navneet S.; C. KOH, Mickey B.; KHARFAN-DABAJA, Mohamed A.; & CHAO, Nelson J. (2021). Psychosocial and patient support services in comprehensive cancer centers. In Rajshekhar Chakraborty, Navneet S. Majhail, & Jame Abraham (Eds.), The Comprehensive Cancer Center: Development, Integration, and Implementation (pp. 93-106). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-82052-7_11

6

BARTH, Juerguen; & Patrizia LANNEN (2011). Efficacy of communication skills training courses in oncology: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Oncology, 22(5), 1030-1040. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdq441

7

BASHKIN, Osnat; ASNA, Noam; AMOYAL, Mazal; & DOPELT, Keren; (2023). The role of nurses in the quality of cancer care management: Perceptions of cancer survivors and oncology teams. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 39(4), Article e151423. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SONCN.2023.151423

8

BRAU-FIGUEROA, Hasan; PALAFOX-PARRILLA, E. Alejandra; & MOHAR-BETANCOURT, Alejandro (2020). El registro nacional de cáncer en México, una realidad. Gaceta Mexicana de Oncología, 19(3), 107-111. https://doi.org/10.24875/J.GAMO.20000030

9

CANTÚ-QUINTANILLA, Guillermo Rafael; AGUIÑAGA-CHIÑAS, Nuria; & FARÍAS-Yapur, Anneke (2021). Nursing personnel training: A pilot study on attitude change, through a workshop on ethics and humanities. Revista de Estudios e Investigacion en Psicologia y Educacion, 8(2), 198-210. https://doi.org/10.17979/reipe.2021.8.2.8397

10

CARRERAS MARCOS, Bernat; ESQUERDA ARESTE, Montse; & RAMOS POZÓN, Sergio (2021). Formación en comunicación para profesionales sanitarios. Revista de Bioética y Derecho, 52, 29-44. https://doi.org/10.1344/RBD2021.52.34218

11

12

COHEN, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Taylor and Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

13

COOK, Rebecca. S.; GILLESPIE, Gordon L.; KRONK, Rebeca; DAUGHERTY, Margot C.; MOODY, Suzzane. M.; ALLEN, Lesley. J.; SHEBESTA, Kaaren B.; & FALCONE, Richard A. (2013). Effect of an educational intervention on nursing staff knowledge, confidence, and practice in the care of children with mild traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 45(2), 108-118. https://doi.org/10.1097/JNN.0B013E318282906E

14

CROCCO, Ingrid M.; GOODLITT, Lucille; & PARKOSEWICH, Janet A. (2023). The effect of an educational intervention on nurses’ knowledge, perception, and use of nursing presence in the perioperative setting. Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing, 38(2), 305-311. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JOPAN.2022.06.005

15

DIAZ F., Eu Marcela; GATTAS N., Eu Sylvia; LOPEC C., Eu Juan Carlos; & TAPIA M., Eu Aracely (2013). Enfermería oncológica: Estándares de seguridad en el manejo del paciente oncológico. Revista Médica Clínica Las Condes, 24(4), 694-704. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0716-8640(13)70209-8

16

DOS SANTOS, Fabiana Cristina; CAMELO, Silvia Helena Henriques; LAUS, Ana María; & LEAL, Laura Andrian (2015). El enfermero de unidades hospitalarias oncológicas: Perfil y capacitación profesional. Enfermería Global, 14(38), 301-312. https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1695-61412015000200016

17

GÓMEZ-Lucio, María del Carmen (2023). Cuidado humanizado del profesional de enfermería en la atención del paciente oncológico hospitalizado. Revista de Enfermería Neurológica, 22(1), 31-46. https://doi.org/10.51422/REN.V22I1.421

18

GUEVARA-VALTIER, Milton Carlos; SANTOS-FLORES, Jesús Melchor; SANTOS-FLORES, Izamara; VALDEZ-RAMIREZ, Francisca Julieta; GARZA-DIMAS, Iris Yazmany; PAZ-MORALES, María de los Ángeles; & GUTIÉRREZ-VALVERDE, Juana Mercedes (2017). Conocimiento de enfermería sobre cuidados paliativos en centros de primer y segundo nivel de atención para la salud. Revista CONAMED, 22(4), 170-173. https://www.medigraphic.com/cgi-bin/new/resumen.cgi?IDARTICULO=79259

19

GUSTAFSSON, Markus; & BORGLIN, Gunilla (2013). Can a theory-based educational intervention change nurses’ knowledge and attitudes concerning cancer pain management? A quasi-experimental design. BMC Health Services Research, 13(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-328

20

HARDEN, Karen; PRICE, Deborah; DUFFY, Elizabeth A.; GALUNAS, Laura; & RODGERS, Cheryl C. (2017). Palliative care: Improving nursing knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 21(5), E232-E238. https://doi.org/10.1188/17.CJON.E232-E238

21

HOWELL, Doris; MCGOWAN, Patrick; BRYANT-LUKOSIUS, Denise; KIRBY, Ryan; POWIS, Melanie; SHERIFAL, Diana; KRUKETI, Vishal, RASK, Sara; & KRZYZANOWSKA, Monica K. (2023). Impact of a training program on oncology nurses’ confidence in the provision of self-management support and 5As behavioral counseling skills. Cancers, 15(6), Article 1811. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15061811

22

KOVNER, Christine. T.; DJUKIC, Maja; JUN, Jin; FLETCHER, Jason; FATEHI, Farida. K.; & BREWER, Carol S. (2018). Diversity and education of the nursing workforce 2006-2016. Nursing outlook, 66(2), 160-167. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.OUTLOOK.2017.09.002

23

KURNIASIH, Yuni; MELINDA, Dina; & RAMDHANI, Wawan Febri (2025). Demographic factors and marital status: Do they really influence the quality of nursing work life? Malahayati International Journal of Nursing and Health Science, 7(12), 1501-1506. https://doi.org/10.33024/MINH.V7I12.715

24

LAKENS, Daniel (2013). Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, Article 863. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863

25

MEDINA ZARCO, Lilia E.; DE LA CRUZ CASAS, Angélica María; SÁNCHEZ SANTAELLA, Martha Elba; & PEDRAZA ÁVILES, Alberto González (2012). Nivel de conocimientos del personal de salud sobre cuidados paliativos. Revista de Especialidades Médico-Quirúrgicas, 17(2), 109-114. https://www.medigraphic.com/cgi-bin/new/resumen.cgi?IDARTICULO=35158

26

MISUN, Jeon; KIM, Sue; & KIM, Sanghee (2023). Association between resilience, professional quality of life, and caring behavior in oncology nurses: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 53(6), 597-609. https://doi.org/10.4040/JKAN.23058

27

MOHAMMED, Heba Sayed; MOHAMMAD, Zienab Abd-lateef; & KHALLAF, Salah Mabrouk (2023). Impact of in- service training program on nurses’ performance for minimizing chemotherapy extravasation. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 24(10), 3537-3542. https://doi.org/10.31557/APJCP.2023.24.10.3537

28

MONTAÑEZ-HERNÁNDEZ, Julio César; ALCALDE-RABANAL, Jaqueline Elizabeth; NIGENDA-LÓPEZ, Gustavo Humberto; ARISTIZÁBAL-HOYOS, Gladis Patricia; & DINI, Lorena (2020). Gender inequality in the health workforce in the midst of achieving universal health coverage in Mexico. Human Resources for Health, 18, Article 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12960-020-00481-Z

29

MORALES-CASTILLO, F. A.; HERNÁNDEZ-CRUZ, M. C.; MORALES RODRIGUEZ, M. C.; & LANDEROS OLVERA, E. A. (2016). Validación y estandarización del instrumento: Evaluación de los comportamientos de cuidado otorgado en enfermeras mexicanas. Enfermería Universitaria, 13(1), 3-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reu.2015.11.005

30

NAKAZAWA, Y.; MIYASHITA, M.; MORITA, T.; UMEDA, M.; OYAGI, Y.; & OGASAWARA, T. (2009). The palliative care knowledge test: Reliability and validity of an instrument to measure palliative care knowledge among health professionals. Palliative Medicina23(8), 754-766. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216309106871

31

ORDOÑEZ MOLERO, Diego Alejandro; RIVERA MUÑOZ, Andrés Eduardo; & MATELUNA PAREDES, Paulo Cesar (2018). Nivel de conocimientos acerca de cuidados paliativos en alumnos de medicina de sexto año de la Universidad Peruana. [Trabajo de Investigación para la obtención del Título Profesional de Médico Cirujano, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia]. Repositorio Institucional de la Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia. https://repositorio.upch.edu.pe/handle/20.500.12866/1505

32

ORGANIZACIÓN PANAMERICANA DE LA SALUD & ORGANIZACIÓN MUNDIAL DE LA SALUD (2024). Enfermedades no transmisibles. https://www.paho.org/es/temas/enfermedades-no-transmisibles

33

PARAJULI, Jyotsana; & HUPCEY, Judith (2021). A systematic review on oncology nurses’ knowledge on palliative care. Cancer nursing, 44(5), E311-E322. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000817

34

PONTI, E.; SAEZ, N.; ANGELONI, L. S.; ÁLVAREZ, M.; MINCONE, F.; & CICERONE, F. (2019). Nursing knowledge for assessment and permanent surveillance of symptoms in palliative care. Revista Cubana deEducación Médica Superior, 33(3), Article e1642. https://www.medigraphic.com/cgi-bin/new/resumenI.cgi?IDARTICULO=93204

35

REYNAGA-ORNELAS, Luxana; DÍAZ-GARCÍA, Nancy Yadira; GONZÁLEZ-FLORES, Alma Delia; MEZA-GARCÍA, Carlos Francisco; & RODRÍGUEZ-MEDINA, Rosa María (2022). Evaluación de los comportamientos de cuidado humano de las enfermeras: Perspectiva de personas adultas hospitalizadas. Metas de enfermería, 25(4), 5-13. https://enfispo.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=8415410

36

37

SAPRI, Nur Diyana; NG TING, Yan; & KLANIN-YOBAS, P. (2022). Effectiveness of educational interventions on evidence-based practice for nurses in clinical settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurse Education Today, 111, Article 105295. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NEDT.2022.105295

38

SECRETARÍA DE SALUD (2023, 16 de septiembre). México registra al año más de 195 mil casos de cáncer: Secretaría de Salud. https://www.gob.mx/salud/prensa/294-mexico-registra-al-ano-mas-de-195-mil-casos-de-cancer-secretaria-de-salud

39

SHELDON, Lisa K.; & BOOKER, Reanne (2023). Growth and development of oncology nursing in North America. Annals of Palliative Medicine, 12(5), 1016-1025. https://doi.org/10.21037/APM-22-1121

40

SMITH, Karen; KRESSEL, Bruce; THORNTON, Katherine; & BISHOP, Catherine (2017). Psycho-oncological education to reduce psychological distress levels in patients with solid tumor cancers: A quality improvement project. Journal of Oncology Navigation & Survivorship, 8(10). https://www.jons-online.com/issues/2017/october-2017-vol-8-no-10/1706-psycho-oncological-education

41

SOLERA-GÓMEZ, Silvia; BENEDITO-MONLEÓN, Amparo; LLINARES-INSA, Lucia Inmaculada; SANCHO-CANTUS, David; & NAVARRO-ILLANA, Esther (2022). Educational needs in oncology nursing: A scoping review. Healthcare, 10(12), Article 2494. https://doi.org/10.3390/HEALTHCARE10122494

42

TABERNA, Miren; GIL MONCAYO, Francisco; JANÉ-SALAS, Enric; ANTONIO, Maite; ARRIBAS, Lorena; VIILLAJOSANA, Esther; PERALVEZ TORRES, Elisabeth; & MESIA, Ricard (2020). The multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach and quality of care. Frontiers in Oncology, 10, Article 85. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.00085

43

VALIZADEH, Leila; ZAMANZADEH, Vahid; AZIMZADEH, Roghaieh; & RAHMANI, Azad (2012). The view of nurses toward prioritizing the caring behaviours in cancer patients. Journal of Caring Sciences, 1(1), 11-16. https://doi.org/10.5681/JCS.2012.002

44

YOUNG, Annie M.; CHARALAMBOUS, Andreas; OWEN, Ray I.; NJODEZEKA, Bernard; OLDENMENGER, WENDY H.; & ALQUDIMAT, Mohammad R. (2020). Essential oncology nursing care along the cancer continuum. The Lancet Oncology, 21(12), e555-e563. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30612-4