The education system in Turkey has a central management feature. Curriculums are developed by the central management. Elementary, middle, and high school curriculums are developed by the Turkish Ministry of National Education (TMNE). Teacher training programs are also developed by the Council of Higher Education (CHE). These curriculums are implemented similarly in all schools in Turkey. The CHE began the process of reorganizing educational faculties in 1998. New teacher training programs were published in 1998, 2006, and 2018 (). In Turkey, all faculties of education follow the current curriculum, and the program lasts four years. Introduction to education, educational psychology, educational sociology, measurement and evaluation in education, teaching principles and methods, classroom administration, teaching technology, and so on was covered in the first three years. The last year of the curriculum emphasizes the Teaching Practice Course in school settings, when trainees are sent to classrooms to conduct lessons and learn about school procedures.

The Teaching Practice Course is designed to provide Turkish prospective teachers with teaching experience. This course covers the teaching applications in the TMNE’s state schools in the teaching sector. Prospective teachers in all disciplines have the ability to apply their qualifications in a real-world setting similar to the teaching career that they have learned about in the faculty of education through this course (). Prospective teachers have to enter the classroom for 6 hours a week for two semesters under the supervision of a supervisor (teacher) and give lectures to the students of elementary, middle, and high schools.

In the context of teacher education, teaching practice is a necessary field practice experience in which prospective teachers apply the knowledge and skills they have learned in real classroom settings. Teaching quality and student accomplishment are determined by the teacher's employment of various teaching technics and instructional materials chosen and employed in line with instructional goals, an instructional framework customized to students' needs, and good interaction formed with students. Teachers who demonstrate these efficiencies are referred to as successful teachers (; ). In short, prospective teachers should gain these skills through theory and practice during their training and believe that they can teach effectively and deal with difficulties in their future careers.

Even though prospective teachers do not have the same responsibilities and duties as in-service teachers, they practice in the classroom (under supervision) for the first time. At the same time, prospective teachers may be anxious about writing lesson plans, choosing and using teaching techniques and strategies, and managing and maintaining discipline in the classroom (). While supervision encourages professional development on the one hand, it can also be a source of stress due to the evaluation of students during teaching practice (). The assistance and support offered by university and school supervisors have a considerable impact on the productivity and efficacy of teaching practices. point out that supervision plays an important role in prospective teachers' socialization process, learning and professional development, as well as on their emotional and physical balance. The supervisor (peer, the university and school supervisors) is a key element in teaching practice, as a supporter and guide of the learning to teach process and an important source of emotional support ().

In this research, it is aimed to determine whether self-efficacy levels are significantly involved as a mediating variable in the relationship between prospective teachers’ perceived social support and classroom stress levels. In Turkey, many studies have been conducted on prospective teachers' stress levels (e.g. ), coping styles (e.g. ), perceived social support (), self-efficacy beliefs and resources (). However, no study has been found in the Turkish literature that examines prospective teachers' classroom stress, self-efficacy and perceived social support variables together. The outcomes of this study are expected to inform teacher trainers in university teacher education departments as steps are implemented and goals are set to reduce prospective teachers' classroom stress. In addition, the content of this study is believed to contribute to the improvement of the quality of teaching practice courses in teacher training programs.

Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

Teacher stress

Teacher stress is described as an unpleasant, negative feeling experienced by a teacher as a result of some part of their profession as a teacher, such as anger, anxiety, tension, frustration, or sadness (). There are three major dimensions of stress causing these negative emotions: The first is stress sources. These are the events happening in the workplace. For example, disruptive and boisterous student group or rude and argumentative parents are stress sources the teachers can encounter in the workplace. The second dimension includes the psychological (fear, anxiety, anger, aggression, and so on.) and physiological (increased muscle tension, increased heart rate) effect of stressor on the individual. The third dimension is evaluating a present stressor as threatening or harmful ().

Teachers report specific stressors lack of motivation in students, managing student behaviour, lack of resources and support, workload, coping with changes, evaluations from administration, interactions with colleagues, poor working conditions (e.g. ; ; ). Excessive stress has a negative influence on teachers' performance, career possibilities, physical and mental health, and overall job happiness (). Stress in teachers manifest itself psychologically as sudden anger, depression seizures, constant state of tension, anxiety and instability; physiologically as headaches, fatigue, digestive disorders, insomnia, cardiovascular disease and substance abuse (; ). Teachers' behaviour is clearly affected by stress, which may diminish their efficiency in the classroom, resulting in unfavourable academic and behavioural consequences for children (). According to , instructors who are stressed or burned out feel less connected to their pupils and use more reactive and punitive methods to regulate student behaviour in the classroom.

In pre-professional, prospective teachers encounter the stress sources described above when they go to schools practice teaching. Studies with prospective teachers reported the similar stress factors (). In Chaplain's () study, prospective teachers reported behaviour management, teaching workload and lack of support as important factors affecting their stress levels. In addition, not being told exactly what is expected of them by university and school supervisors and not giving prompt and constructive feedback can be a source of stress for prospective teachers (; ). found that poor relationship between school supervisor and prospective teachers is a concern that negatively impacts on motivation to enter the profession of prospective teacher.

Teacher stress and social support

Social support may be characterized as social exchange processes that help people develop their behavioural patterns, values, and social cognitions (). Social support has beneficial effects on physical and psychological health (; ; ) and reduces work stress (). Two different models are proposed on the effect of social support on health. First model, main-effect model, suggests a direct relationship between social support and health. According to this model, social support has a positive effect on physical health and wellbeing under any circumstances and lack of social support would have a negative effect on the individual (). This influence can come in a variety of shapes and sizes. According to , social support and stress can have both a good and negative association. In other words, when a person has less social support, their stress levels will rise, or support providers will intervene and boost social support when the person is stressed. Second model is the stress-buffering model. According to stress-buffering model, the most important function of social support is to protect the mental health of the individuals by reducing the negative effect caused by stressful life events. Not having social support does not have any negative effect on the individual as long as he or she does not encounter stressful life events (). In this context, the support they will receive from their peers and university supervisor during their teaching practice, which is a stressful experience for prospective teachers, will reduce their stress levels.

Teacher stress and self-efficacy

Self-efficacy is defined by as an individual's assessment of his or her own ability to plan and execute the steps required to display a certain performance. The amount of labour teachers put into teaching, the expectations they set, and their feeling of desire are all influenced by their self-efficacy ideals (). When dealing with adversity, the construct of self-efficacy indicates a defensive effect. Self-efficacious instructors, on the other hand, would regard the objective demands of everyday instruction as less intimidating than instructors who have misgivings about their professional abilities (). Teachers with high efficacy are emotionally robust and can steer their attention toward overcoming issues when faced with stress, while teachers with low efficacy concentrate on relieving their emotional distress ().

Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs and their influence on stress have also been examined and self-efficacy has been found to be negative related to stress (; ; ). According to Schmitz and , self-efficacy belief is a protective factor against occupational stress, and instructors who have a high degree of self-efficacy gravitate more into their profession and are happier. For this reason, state that it is important to increase prospective teachers' self-efficacy during teaching practice in order to train resilient teachers before they start to work. According to , mastery experiences (i.e., experience gained from teaching practice), vicarious experiences (i.e., experience gained by observing peers and school supervisor), and verbal persuasion (i.e., constructive feedback provided by their peers and supervisors) are significant sources of teaching self- efficacy of prospective teachers. Previous research shows that university supervisors improve their teaching self-efficacy when they provide positive feedback to prospective teachers and support their autonomy (e.g. ; ; ).

Teacher stress, social support and self-efficacy

Prospective teachers' experience anxiety in four areas: preparation and implementation of lesson plans, classroom management, evaluation of lessons, and relationships with school staff (). Studies in the teacher education literature have provided evidence for the positive results of providing social support in a variety of settings. Supervisor's visit and constructive feedback provided by peers and supervisors may be the ways to provide social support for pre-service teachers (). Research findings in this field points out the important role of supervision (; ; ) and peer feedback () on pre-service teachers' emotional balance. found that pre-service teachers' initial experiences of uneasiness and anxiety during teaching practice, which can contribute to stress, are reduced by the presence of the support system.

In the related literature, it is stated that there is a positive relationship between perceived social support and self-efficacy belief. In their work, found that teachers' perceived lack of support from their colleagues and principals has a significant effect on their self-efficacy beliefs about getting support from them, and these self-efficacy beliefs predict their burnout levels. This result means that when the teachers perceive low support from their administrators and colleagues, they trust less to their own capacities. The opposite is also true. When the teachers perceive high support from their administrators and colleagues, they trust more to their own capacities.

According to , social support is an important determinant of high or low self-efficacy. Furthermore, larger levels of perceived social support, according to social cognition theory, may boost self-efficacy views through verbal persuasion from others, alleviating some of the negative impacts of low self-efficacy (; ). As a result, larger levels of social support are linked to better levels of personal self-efficacy, forming a "resource caravan" to combat stresses (; ; ; ). In the literature, there are findings related to the mediator role of self-efficacy belief between perceived social support and wellbeing () social support and stress (). These findings show that university supervisor and peer support can act as a 'buffer' in reducing the stress levels that prospective teachers often experience during their teaching practices by increasing their self-efficacy.

The present study

As be seen from the explanations above, teacher stress in the classroom is related both to teacher self-efficacy and to social support. Considering the relationship between teacher self-efficacy and social support, we thought that pre-service teachers will be more confident in their own capacities with the perceived social support (constructive feedback) from their supervisors and peers, and thus them in-class stress will be reduce. In this research, we examined the mediating role of teacher self-efficacy (Efficacy for student engagement, Efficacy for instructional strategies, and Efficacy for classroom management) in the relationship between prospective teachers' perceived social support (Teacher support and Classmate support) and classroom stress levels. Therefore, this research proposed the following hypotheses.

-

H1: Perceived social support (Teacher and classmate support) will negatively and directly predict stress in classroom.

-

H2: Perceived social support (Teacher and classmate support) will significantly and indirectly predict stress in classroom through teacher self-efficacy (Efficacy for student engagement, Efficacy for instructional strategies, and Efficacy for classroom management).

Hypothesized two path models

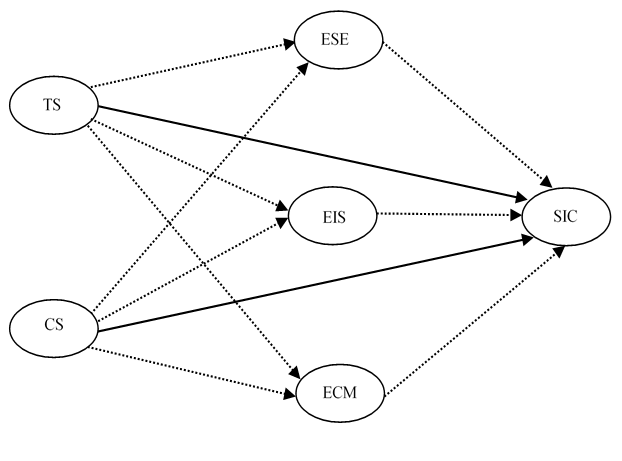

Social support has been demonstrated to be a predictor of self-efficacy in many studies (e.g. ; ; ). However, there are findings related to the mediator role of self-efficacy belief between perceived social support and wellbeing () and stress (). Two models were constructed in response to the conflicting results found in previous studies on the relationship between self-efficacy, social support, and stress. To examine these relationships, two path models were proposed for all relationships between two latent variables (Teacher support = TS, and Classmate support = CS) and one latent variable (Stress in classroom = SIC), and with the predicted relationships, and with mediating role of three latent variables (Efficacy for student engagement = ESE, Efficacy for instructional strategies = EIS, and Efficacy for classroom management=ECM) in these relationships. In the hypothesized Model 1, it was considered that the SSS subscales (TS and CS) both directly and indirectly via Teacher’ Sense of Efficacy Scale (TSES) subscales predicted SIC; on the other hand, in the hypothesized Model 2, it was thought that the SSS subscales predicted SIC directly. The model of hypothesized structural relationships is shown in Figure 1.

Note: Dashed lines show that the SSS subscales (TS and CS) indirectly via TSES subscales ESE, EIS, and ECM) predicted SIC (Model 1), while solid lines represent that the SSS subscales directly predicted SIC (Model 2).

Method

Participants

The participants included 725 prospective teachers from five different universities in Turkey. 17.8% (f = 129) of the prospective teachers were from the Mediterranean region; 28% (f = 203) were from Western Anatolian region; 20.8% (f = 151) were from Mid-Southern Anatolia. The prospective teachers were from different departments like Turkish language teaching, science and technology education, elementary school teaching, social studies education, and visual arts education, music education, and physical education and sports teaching. Of them, 57.5% (f = 417) were female and 42.5% (f = 308) were male. The ages of the prospective teacher ranged from 20 to 30 years old (M = 22.49, SD = .04).

Instruments

Prospective teachers filled out some demographic information such as age, gender, department, and university name. They took three paper-based inventories. First, they filled out the Teacher’ Sense of Efficacy Scale (TSES) (), second they did the Teacher Stress Inventory (TSI) (), and third they did the Social Support Scale (SSS) ().

Teacher sense of efficacy scale

Tschannen-Moran and created the Teachers Sense of Efficacy Scale (TSES), which translated to Turkish. The scale is divided into three sub-dimensions, each with eight objects. The first metric assesses the teacher's ability to motivate students. The teachers' effectiveness for instructional methods is measured on the second scale, and their efficacy for classroom administration is measured on the third dimension. The points changed from 1-nothing to 9- A Great Deal, The following are some examples of TSES items: Efficacy for Student Engagement- “How much can you do to get students to believe they can do well in schoolwork?”, Efficacy for Instructional Strategies- “To what extent can you use a variety of assessment strategies?”, Efficacy for Classroom Management- “How much can you do to control disruptive behaviour in the classroom?” (). There are many studies showing that this scale was applied to prospective teachers after it was adapted to Turkish (e.g. ; ).

Stress in classroom scale

Developed by , Teacher Stress Inventory (TSI) scale has a four-factor structure. First factor Stress in Classroom (SIC) dimension is made up of 11 items; second factor Professional Distress is made up of 3 items; third factor Emotional Fatigue Manifestations is made up of 10 items; and fourth factor Biobehavioural Manifestations is made up of 8 items. Because of the focus point of this study, only the Stress in Classroom dimension was used in this study. The points changed from 1-Strongly Disagree to 5-Strongly Agree. The followings are two sample items from the SIC: “Discipline problems in the classroom” and “Teaching poorly motivated students”. The scale was translated into Turkish after researchers' discussions and later translated back to English. Scale's Turkish and English language compatibility was checked and using a language that would be easily understood by the Turkish prospective teachers became a priority. As a result of exploratory factor analysis, it was determined that the scale was one dimensioned.

Social support scale

Developed by , the Social Support Scale (SSS) has a four-factor structure. Factors are Parent(s) support, Teacher(s) support, Classmate support and Close friend support respectively. Each factor consists of 15 items. Because of the focus point of this study, only the Teacher(s) support and Classmate(s) support dimensions were used in this study. Parent(s) support and Close friend support dimensions of the scale were not included in the study; because, during the teaching practice course, the most of the time, prospective teachers are with their peers and their practice teachers and with similar experiences. The parents and close friends of the prospective teacher may be unfamiliar with the teaching profession. Thus, this study is focused only on the classmate and practice teacher support.

Teacher(s) support dimension is made up of 15 items and the classmate support dimension is made up of 15 items. There are 30 items in total. Each of the 30 items was translated into Turkish by the researchers after discussion and consensus. Later, it was translated back into English to see the harmony in the original English sentence structure. The items constituting these subscales were adapted to the prospective teachers by staying true to the original structure of the scale. The items that make up the teacher support and classmate support sub-scales were applied to prospective teachers who will start teaching practice, who are university students, as a pre-application. The followings are sample items and adapted items from the SSS: Teacher(s) Support- “Helps me when I want to learn to do something better” and adapted version is “Helps me when I want to learn to do better my teaching role”. Classmate Support- “Help me with projects in class” and adapted version is "Helps me with my teaching role in class". The scales were used with five-points for this study. The points changed from 5-All the time to 1-Never.

Procedure

This study did not undergo institutional review board approval, as it was not necessary. However, the study adhered to the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration. Furthermore, before implementing the measures, the participants were provided with information regarding the objective of the study by the author(s). Prospective teachers were queried about their willingness to volunteer for the study. Subsequently, the measures were administered solely to the prospective teachers who volunteered. Prior to carrying out the measures, informed consent was obtained from all participants. The administration process lasted approximately 12 min for the TSES, 10 min for the SSS (teacher and classmate support dimensions), and 6 min for the SIC. The prospective teachers filled the instruments using pencil.

Data Analysis

Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFA) were performed in AMOS 18 software utilizing the maximum likelihood estimation approach. In the first CFA, the TSES model (i.e., efficacy for student engagement, efficacy for instructional strategies, and efficacy for classroom management) was tested. The SSS model (i.e., teacher support and classmate support) was tested in the second CFA. The one-factor SIC model with 11 indicators was checked in the third CFA.

To see whether demographic factors had a major impact on the scales, ANCOVA and MANCOVA analyses were conducted. A zero-order and partial correlation analyses were used to see if there were any significant relationships between the variables in the model. The structural equation modelling (SEM) analysis was performed in order to test the mediating roles of the ESE, EIS, and ECM (; ). In the SEM analysis, two models were tested using AMOS 18 software. In the first model, SSS subscales predicted SIC both directly and indirectly through the ESE, EIS, and ECM; in the second model, SSS subscales predicted SIC directly. CMIN/ was used to assess model adequacy, RMR, RMSEA, NNFI, as well as the lower and upper confidence intervals (; ). Furthermore, the linearity, singularity, and multicollinearity assumptions were fulfilled among the key assumptions for SEM analysis. The multivariate kurtosis was .06 and critical ratio was .08 (kurtosis for subscales of the TSES: ESE = .07, ESI = .36, and ECM = .29 in absolute value; for subscales of the SSS: TS = .10 and CS = .58; and kurtosis for SIC = .12) showed that the data distributions were similar to average, since higher critical ratio values than 5.00 are representative of data that are non-normally distributed (; ). Mahalanobis d2 ranged from 9.58 to 23.84 (p > .05). Due to the non-significant p-values of the Mahalanobis d2, no multivariate outliers were identified, and the assumption of normality was considered to be met. With these findings, the scales were hypothesized into the model. Hence, Maximum Likelihood Method in the SEM analysis was conducted for the current data. The model was examined that the SSS subscales both directly and indirectly via the TSES subscales predicted SIC.

Results

Preliminary analyses

The factor structure of the TSES subscales

In order to verify the factor structure of the TSES in the current study, CFA was used to evaluate the measurement model (i.e., ESE, EIS, and ECM). The CFA results demonstrated that the measurement model had a significantly good fit ( (222) = 585.30; /df = 2.64; RMR = .02; RMSEA = .05; NNFI = .85). The TSES items were greatly estimated by their latent variables, with standardized parameter estimates ranging from .38 to .61 (all ps < .001). The scales' internal reliabilities varied between .70 and .79. The measurement model (i.e., ESE, EIS, and ECM) was taken into account in this study for this reason as well as the scope of the research. Based on the CFA results, it was concluded that this scale might be used with prospective teachers.

The factor structure of the social support scale’s subscales

Again, in order to validate the factor structure of the SSS in the current sample, CFA was used to test measurement model. CFA was used to evaluate the measurement model (i.e., TS and CS). The CFA findings showed that measurement model had a significantly good fit ( (361) = 1054.21; /df = 2.92; RMR = .03; RMSEA = .05; NNFI = .92). The standardized parameter estimates varied between .60 and.77. The SSS items were strongly predicted by their latent variables (all ps < .001). The internal reliabilities of the scales ranged from .90 to .94. Hence, the measurement model (i.e., TS and CS) were considered in the present study. According to the results of CFA, it was decided that this scale could be applied to prospective teachers.

The factor structure of the stress in classroom scale

The CFA findings demonstrated that the one-factor SIC model with 11 items fitted the data well ( (27) = 74.12; /df = 2.74; RMR = .02; RMSEA = .04; NNFI = .96). The standardized parameter estimations ranged from .30 to .72. McDonald's Omega (ω) was measured to be .77 for the scale's internal consistency. This signifies that the items in the SIC were considerably predicted by their latent variables (all ps< .001). It was agreed that this scale might be used with prospective teachers in light of the CFA results.

Effects of demographic variables on SIC, SSS subscales (TS and CS), and TSES subscales (ESE, EIS, and ECM)

MANCOVA results showed that the effects of age ( = .02), gender ( = .01), department ( = .05), and University ( = .03) on the TSES subscales were unimportant. ANCOVA results demonstrated that the effects of age ( = .01), gender ( = .00), and department ( = .03) on SIC were unimportant and University ( = .08) was unimportant. Finally, MANCOVA results showed that the effects of age ( = .02), gender ( = .01), department ( = .05), and University ( = .03) on SSS subscales were negligible. Although demographic variables had minor effects on the SIC, SSS subscales, and TSES subscales, a partial correlation analysis and a zero-order correlation analysis were conducted to see if the relationships between the variables were significantly altered as a result of the potential effects of demographic variables. The effects of the partial correlation and zero-order correlation tests are shown in Table 1.

| Variables | M | SD | ESE | EIS | ECM | TS | CS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESE | 30.34 | 3.13 | -- | ||||

| EIS | 30.61 | 3.26 | .62*(.62*) | -- | |||

| ECM | 30.67 | 3.50 | .63*(.63*) | .62* (.62*) | -- | ||

| TS | 57.34 | 9.27 | .28*(.28*) | .25* (.24*) | .30* (.30*) | -- | |

| CS | 58.63 | 10.67 | .32*(.32*) | .25* (.25*) | .30* (.30*) | .47* (.47*) | -- |

| SIC | 23.06 | 5.24 | -.25*(-.25*) | -.27* (-.27*) | -.24* (-.24*) | -.37* (-.37*) | -.40* (-.40*) |

Note; ESE = Efficacy for student engagement; EIS = Efficacy for instructional strategies;

ECM = Efficacy for classroom management; TS = Teacher support; CS = Classmate support;

SIC = Stress in classroom. Partial correlations are in parentheses and italics after

the demographic variables have been controlled. Zero-order correlations are outside

the parentheses.

*p < .001

As shown in Table 1, including demographic variables in the study had no major impact on the overall view of the relationships between SIC, SSS subscales (TS and CS), and TSES subscales (ESE, EIS, and ECM). As a result, the demographic variables were not taken into account any further. Importantly, with the exception of the relationships between SIC and ESE (r = -.25), SIC and EIS (r = -.27), and ECM (r = -.24), all correlation coefficients ranged from negative moderate (r = -.40) to positive moderate (r = .63) (Table 1). Because of the significant relationships between the SIC, SSS subscales (TS and CS), and TSES subscales, it is fair to investigate the mediating roles of TSES subscales (ESE, EIS, and ECM) in relationships between the SIC and SSS subscales (TS and CS).

The mediating role of the ESE, EIS, and ECM

Results of SEM analysis

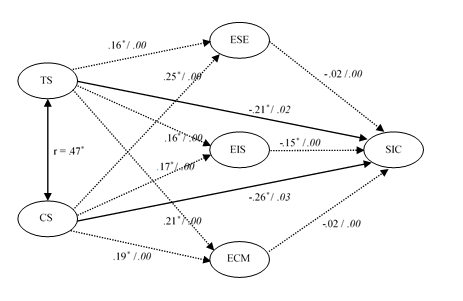

The results of the SEM analysis revealed that the hypothesized first model, in which the SSS subscales (TS and CS) both directly and indirectly through TSES subscales (ESE, EIS, and ECM) predicted SIC, fit the data better ( (1) = 0.01; /df = 0.01; RMR = .00; RMSEA = .03; NNFI = 1.00) than the second model in which the SSS subscales directly predicted SIC ( (1) = 187.95; /df = 187.95; RMR = 19.68; RMSEA = .50; NNFI = .47). The result of the SEM analysis is summarized in Table 2. Figure 2 presents the standardized regression weights of the direct and indirect effects.

As shown in Table 2, TS and CS significantly and negatively predicted SIC (for TSβ = -.21, t = -5.56, p < .001; for CSβ = -.26, t = -6.95, p < .001). SSS subscales (TS and CS) significantly and positively predicted TSES subscales (ESE, EIS, and ECM); however, only EIS from the TSES subscales significantly and negatively predicted SIC (ESE-β = .02, t = .48, p > .05; EIS-β = .15, t = -3.38, p < .001; ECM-β = -.01, t = -.35, p > .05).

| Variables | Variables | Estimate | S.E. | S.R.W. | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECM | <--- | CS | .063 | .013 | .19 | 4.86* |

| EIS | <--- | CS | .053 | .012 | .17 | 4.26* |

| ESE | <--- | CS | .073 | .012 | .25 | 6.31* |

| ESE | <--- | TS | .056 | .013 | .16 | 4.17* |

| EIS | <--- | TS | .058 | .014 | .16 | 4.04* |

| ECM | <--- | TS | .081 | .015 | .21 | 5.39* |

| SIC | <--- | ESE | -.037 | .077 | -.02 | -.48 |

| SIC | <--- | EIS | -.246 | .073 | -.15 | -3.38* |

| SIC | <--- | ECM | -.024 | .069 | -.01 | -.35 |

| SIC | <--- | TS | -.119 | .021 | -.21 | -5.56* |

| SIC | <--- | CS | -.130 | .019 | -.26 | -6.95* |

Note: Dashed lines indicate indirect effects through ESE, EIS, and ECM whereas solid lines indicate direct effects. All parameter estimations in figure are standardized; italics numbers show the results of indirect effect (Model 1), regular numbers show the result of direct effect (Model 2). The correlation coefficient between TS and CS is .47.

*p < .001

As shown in Figure 2, the direct effects of SSS subscales on SIC were significance (i.e., for the TSβ = -.21, p <.001; and for the CSβ = -.26, p <.001). When TSES subscales (ESE, EIS, and ECM) were included in the hypothesized first model SEM analysis, the parameter estimations were not significance, which represented the indirect effects of SSS subscales (TS and CS) on SIC for the TS (β = -.02, p > .05) and the CS (β = -.03, p > .05). This means that the relationships between SIC and teacher support and classmate support were fully mediated by the EIS.

Discussion

This study hypothesized that prospective teachers will be more confident in their own capacities with the perceived social support (constructive feedback) from their supervisors and peers, and thus them in-class stress will be reduce. To test this hypothesis, relationships between five Turkish Universities’ faculty of education's 4th year students' (senior students) teacher self-efficacy beliefs, stress in classroom and perceived social support were examined with ANCOVA, MANCOVA, and SEM analysis. In the pre-analysis, it was found that demographic variables had no significant effect on the scales scores. Therefore, demographic variables were left out of the hypothesized model.

First hypothesis of our study was that perceived social support (Teacher and classmate support) will negatively and directly predict stress in classroom. Current study results showed that teacher stress in the classroom is negatively and significantly correlated with perceived social support (TS and CS subscales), which was an expected result. Previous research findings also supported the idea that social support reduces stress (; ; ; ). In studies specifically focusing on the relationship between stress and social support in the teaching profession, it is stated that teachers with high social support level have better mental and physical health (). specifies that social support has positive effect on wellbeing and physical health under all circumstances and lack of social support have negative effect on the individual. This is also true for prospective teachers. Ways of providing social support to prospective teachers are university supervisor's practice school visits, supervisors' (university and school) observations of practice, and constructive feedback provided by classmates/peers and supervisors (). Related studies report that supervisor' visits (), constructive feedback provided by classmates/peers () and supervisors (; ; ) reduce the stress experienced by prospective teachers during teaching practice.

Second hypothesis of our study was that perceived social support (TS and CS) will predict stress in classroom through the indirect effect of teacher self-efficacy (ESE, EIS and ECM). As a result of the analysis, it was determined that while the social support predicted teacher self-efficacy belief (ESE, EIS, and ECM subscales) positively, it predicted teacher stress in classroom negatively. While the EIS significantly and negatively predicted the SIC, the ESE and ECM were negatively but not significantly predicted the SIC. Prospective teachers attend practice courses with their school supervisor (practice teachers). Therefore, prospective teachers may not have problems in engaging students and classroom management. As a result, it is assumed that prospective teachers' self-efficacy in classroom management and student engagement do not induce stress in the classroom. However, the self-efficacy for instructional strategies requires only the prospective teachers’ own knowledge and skills. So, their self-efficacy for instructional strategies may lead to an increase their stress in the classroom. These results indicate that one way to increase prospective teachers' self-efficacy beliefs is to encourage them, and that improving their self-efficacy expectations is one way to reduce their stress in the classroom. Supporting the findings of this study, in their work found that when the teachers perceived low support from the administrators and colleagues, they trust their own capacity less and when they perceive high support from the administrators and colleagues, they trust their own capacity more. In the same way, there are many studies that support the negative relationship between self-efficacy and stress (e.g. ; ; ). Especially pre-service teachers with higher self-efficacy experience less stress than those with lower self-efficacy ().

Self-efficacy standards, according to , are assessments of a person's ability to behave in a certain way in order to achieve an objective or cope effectively with stressful circumstances. Furthermore, high self-efficacy is linked to stress control, higher self-esteem, better health, better physical condition, and improved adaptation (). assert that self-efficacy perception has a protective effect when met with difficulties and it increases the motivation to solve problems in constructive ways. According to , the higher the perceived self-efficacy, the higher the objectives people set for themselves and the deeper their commitment to them. That is to say, while teachers with low sense of self-efficacy face threats like lack of discipline, motivation and success in their classrooms, teachers with high sense of self-efficacy feel more adequate to deal with these threats ().

The main result of the current study is that only one of the self-efficacy subscales (EIS) fully mediated the association between social support subscales (TS and CS) and teacher stress in the classroom (SIC). In this study, it is hypothesized that when the prospective teachers' perceived social support from their university and school supervisor and classmates/peers are higher, they will trust their own capacity more and their stress in the classroom will decrease. This hypothesis has been partially confirmed in present study. In previous studies revealed that the mediator role of self-efficacy belief between perceived social support and wellbeing () social support and stress ().

As a result, in the practice courses prospective teachers have never experienced before, increasing of the social support (from supervisors and classmate) has an important role in making them trust their own capacity more, and coping with stress sources they will meet in the classroom. Therefore, before and after the teaching practice course, support groups among the prospective teachers can be created to share their teaching experiences. In this group work, prospective teachers can share the difficulties and challenges they faced during the practice course and how they dealt with these with the other group members. Thus, their self-efficacy may be increased and classroom stress may be lowered by providing classmate support. By organizing seminars for school supervisor (practice teachers) prior to the practice course, they can become an important source of support for the prospective teachers. Furthermore, prior to the practice course psycho-educational group works can be done for prospective teachers to gain skills to cope with their job stress. Additionally, microteaching applications can be used to further prospective teachers’ self-efficacies in classroom management, student engagement, and instructional strategies.

Limitations

There are three limitations to this study that will guide future research. First, the sample included prospective teachers in a variety of educational fields (i.e., social studies education, Turkish language teaching, elementary school teaching, science and technology education, visual arts education, music education, and physical education and sports teaching). For this reason, the conclusions presented here cannot be applied to other disciplines of education. The data were collected from five universities, which is the second limitation. Despite the fact that the universities were pretty much representative of the teacher education in Turkey, they were also a limited sample as compared to other Turkish universities. More research should be done with more prospective teachers from more than five universities to provide more generalizable data. The present data is focused on self-report interventions, which is the final limitation. The responses on the scales will reflect the participants' expectations for the teaching profession rather than their actual intentions. As a result, future research could need to account for the impact of social desirability.

References

1

ALANOĞLU, Müslim (2020). Relationships between teacher candidates' perceived social support levels and attitudes towards learning. SDU International Journal of Educational Studies, 7(2), 305-319. https://doi.org/10.33710/sduijes.753571

2

3

ARSLAN, Şeyda; & ÇOLAKOĞLU, Özgür Murat (2019). The predictive power of pre-service teachers' sources of self-efficacy beliefs on teaching self-efficacy beliefs and attitudes. Karaelmas Eğitim Bilimleri Dergisi, 7(1), 74-83. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/kebd/issue/67223/1049161

4

6

7

BOTTIANI, Jessica H.; DURAN, Chelsea A. K.; PAS, Elise T.; & BRADSHAW, Catherine P. (2019). Teacher stress and burnout in urban middle schools: Associations with job demands, resources, and effective classroom practices. Journal of School Psychology, 77, 36–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2019.10.002

8

BROUWERS, Andre; EVERS, Will J. G.; & TOMIC, Welko (2001). Self-efficacy in eliciting social support and burnout among secondary-school teachers. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31(7), 1474-1491. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb02683.x

9

10

CAIRES, Suzana; & ALMEIDA, Leandro S. (2007). Positive aspects of the teacher training supervision: The student teachers’ perspective. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 22(4), 515–528. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03173469

11

CAIRES, Suzana; ALMEIDA, Leandro S.; & MARTINS, Carla (2009). The socioemotional experiences of student teachers during practicum: A case of reality shock? The Journal of Educational Research, 103(1), 17-27. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220670903228611

12

CAIRES, Suzana; ALMEIDA, Leandro; & VIEIRA, Diana (2012). Becoming a teacher: Student teachers’ experiences and perceptions about teaching practice. European Journal of Teacher Education, 35(2), 163-178. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2011.643395

13

CHAN, David W. (2002). Stress, self-efficacy, social support, and psychological distress among prospective Chinese teachers in Hong Kong. Educational Psychology, 22(5), 557-569. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144341022000023635

14

CHAN, Sokhom; MANEEWAN, Sorakrich; & KOUL, Ravinder (2021). Cooperative learning in teacher education: Its effects on EFL pre-service teachers’ content knowledge and teaching self-efficacy. Journal of Education for Teaching, 47(5), 654-667. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2021.1931060

15

CHAPLAIN, Roland P. (2008). Stress and psychological distress among trainee secondary teachers in England. Educational Psychology, 28(2), 195-209. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410701491858

16

COFFMAN, Donna L.; & GILLIGAN, Tammy D. (2002). Social support, stress and self-efficacy: Effects on students’ satisfaction. Journal of College Student Retention, 4(1), 53-66. https://doi.org/10.2190/BV7X-F87X-2MXL-2B3L

17

COHEN, Sheldon (2004). Social relationships and health. American Psychologist, 59(8), 676-684. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676

18

19

20

DALGARD, Odd Steffen; BJØRK, Sven; & TAMBS, Kristian (1995). Social support, negative life events and mental health. British Journal of Psychiatry, 166, 29-34. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.166.1.29

21

DECARLO, Lawrence T. (1997). On the meaning and use of kurtosis. Psychological Methods, 2(3), 292-307. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.2.3.292

22

23

FARMER, Thomas W.; & FARMER, Elizabeth M. Z. (1996). Social relationships of students with exceptionalities in mainstream classrooms: Social networks and homophily. Exceptional Children, 62(5), 431–450. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440299606200504

24

FIMIAN, Michael J.; & FASTENAU, Philip S. (1990). The validity and reliability of the Teacher Stress Inventory: A re-analysis of aggregate data. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 11(2), 151-157. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030110206

25

GARDNER, Sallie (2010). Stress among prospective teachers: A review of the literature. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 35(8), 18-28. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2010v35n8.2

26

GONZÁLEZ, Antonio; CONDE, Ángeles; DÍAZ, Pino; GARCÍA, Mar; & RICOY, Carmen (2018). Instructors’ teaching styles: Relation with competences, self-efficacy, and commitment in pre-service teachers. Higher Education, 75, 625–642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0160-y

27

28

HANSEN, Jo-Ida; & SULLIVAN, Brandon A. (2003). Assessment of workplace stress: Occupational stress, its consequences, and common causes of teacher stress (ED480078). ERIC. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED480078

29

HEINZ, Manuela (2024). The practicum in initial teacher education – enduring challenges, evolving practices and future research directions. European Journal of Teacher Education, 47(5), 865–875. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2024.2428031

30

HERMAN, Keith C.; HICKMAN-ROSA, Jal’et; & REINKE, Wendy M. (2018). Empirically derived profiles of teacher stress, burnout, self-efficacy, and coping and associated student outcomes. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 20(2), 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300717732066

31

HERMAN, Keith C.; PREWETT, Sara L.; EDDY, Colleen L.; SAVALA, Alyson; & REINKE, Wendy M. (2020). Profiles of middle school teacher stress and coping: Concurrent and prospective correlates. Journal of School Psychology, 78, 54-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2019.11.003

32

HOBFOLL, Stevan E. (2012). Conservation of resources and disaster in cultural context: The caravans and passageways for resources. Psychiatry, 75(3), 227-232, https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2012.75.3.227

33

HOUSE, James S.; UMBERSON, Debra; & LANDIS, Karl R. (1988). Structures and processes of social support. Annual Review of Sociology, 14, 293-318. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.14.080188.001453

34

IACOBUCCI, Dawn; SALDANHA, Neela; & DENG, Xiaoyan (2007). A meditation on mediation: Evidence that structural equations models perform better than regressions. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17(2), 139–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1057-7408(07)70020-7

35

KAUR, Amrita; KABILAN, Muhammad Kamarul; & ISMAIL, Hairul Nizam (2021). The role of support system: A phenomenological study of pre-service teachers’ international teaching practicum. The Qualitative Report, 26(7), 2297-2317. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol26/iss7/14/

36

37

KLASSEN, Robert M. (2010). Teacher stress: The mediating role of collective efficacy beliefs. The Journal of Educational Research, 103, 342-350. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220670903383069

38

39

KYRIACOU, Chris (2001). Teacher stress: Directions for future research. Educational Review, 53(1), 27-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131910120033628

40

LAROCCO, James M.; HOUSE, James S.; & FRENCH, John R. P. (1980). Social support, occupational stress, and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 21(3), 202-218. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136616

41

LEE, Alfred S. Y.; FUNG, Wing Kai; DAEP DATU, Jesus Alfonso; & CHUNG, Kevin Kien Hoa (2024). Well-being profiles of pre-service teachers in Hong Kong: Associations with teachers’ self-efficacy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Reports. 127(3), 1009-1031. https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941221127631

42

MAGUIRE, Meg (2001). Bullying and the postgraduate secondary school trainee teacher: An English case study. Journal of Education for Teaching, 27(1), 95-109. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607470120042564

43

MALECKI, Christine Kerres; & ELLIOTT, Stephen N. (1999). Adolescents’ ratings of perceived social support and its importance: Validation of the Student Social Support Scale. Psychology in the Schools, 36(6), 473-483. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6807(199911)36:6<473::AID-PITS3>3.0.CO;2-0

44

MATOTI, Sheila N.; & LEKHU, Motshidisi A. (2016). Sources of anxiety among pre-service teachers on field placement experience. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 26(3), 304-307. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2016.1185921

45

NAKIP, Can; & ÖZCAN, Gülsen (2016). The relation between preservice teachers’ sense of self efficacy and attitudes toward teaching profession. Mersin University Journal of the Faculty of Education, 12(3), 783-795. https://doi.org/10.17860/mersinefd.282380

46

47

OBERLE, Eva; GIST, Alexander; COORAY, Muthutantrige S.; & PINTO, Joana B. R. (2020). Do students notice stress in teachers? Associations between classroom teacher burnout and students' perceptions of teacher social–emotional competence. Psychology in the Schools, 57, 1741–1756. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22432

48

ÖZAYDIN, Türkan Ercan; ÇAVAŞ, Pınar; & CANSEVER, Belgin Arslan (2017). The evaluation of pre-service classroom teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs. Ege Journal of Education, 18(1), 1-30. https://doi.org/10.12984/egeefd.307303

49

SALTZMAN, Kristina M.; & HOLAHAN, Charles J. (2002). Social support, self-efficacy, and depressive symptoms: An integrative model. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 21(3), 309-322. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.21.3.309.22531

50

SCHMITZ, Gerdamarie Susanne; & SCHWARZER, Ralf (2000). Selbstwirksamkeitserwartung von Lehrern: Längsschnittbefunde mit einem neuen Instrument [Perceived self-efficacy of teachers: Longitudinal findings with a new instrument]. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie / German Journal of Educational Psychology, 14(1), 12–25. https://doi.org/10.1024//1010-0652.14.1.12

51

52

SCHWARZER, Ralf; & HALLUM, Suhair (2008). Perceived teacher self-efficacy as a predictor of job stress and burnout: Mediation analyses. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 57, 152-171. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00359.x

53

54

TONGAL, Ayşegül; & SERT, Hakan (2022). Determining the faculty of the student's received stress and predictions that affect your professional attitude. The Journal of International Education Science, 9(31), 77-100. https://doi.org/10.29228/INESJOURNAL.58138

55

TORRES, José B.; & SOLBERG, V. Scott (2001). Role of self-efficacy, stress, social integration, and family support in Latino college student persistence and health. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 59, 53-63. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2000.1785

56

TSCHANNEN-MORAN, Megan; & WOOLFOLK HOY, Anita (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 783-805. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1

57

VISWESVARAN, Chockalingam; SANCHEZ, Juan I.; & FISHER, Jeffrey (1999). The role of social support in the process of work stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54(2), 314-334. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1998.1661

58

YADA, Akie; BJÖRN, Piia Maria; SAVOLAINEN, Pirjo; KYTTÄLÄ, Minna; ARO, Mikko; & SAVOLAINEN, Hannu (2021). Pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy in implementing inclusive practices and resilience in Finland. Teaching and Teacher Education, 105, Article 103398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103398