Introduction

The Portuguese educational system organizes high school education in three years, preparing students for higher education or labor market. Adolescents must make important decisions regarding their career, which can be challenging and have enduring effects on their trajectories (; ), mainly due to the complexity that characterizes occupational world (), lack of readiness, and career decision-making competencies (). To successfully complete this task, students must engage in a comparative analysis of the available options and select the most suitable alternative. Therefore, career exploration, which entails gathering and evaluating information (; ), is crucial to support informed career decisions () and facilitate the adjustment to new learning or working contexts (; ). Parental support has been considered crucial in promoting adaptive career behaviors (), a view supported by empirical evidence linking greater parental support to higher levels of career exploration () and lower career indecision (). However, in Portugal, despite educational policies encouraging parental involvement, actual engagement remains uneven across families and schools ().

Beyond contextual predictors, increased attention has been given to personal resources that support adolescents’ career exploration (), especially motivational variables (; ; ). Career exploration is considered a goal-oriented behavior that benefits from being analyzed within the motivational frameworks (; ). Flum and underlined that career exploration integrates self-determination mechanisms into career development, since it requires planning and sense of volition and authorship. Following this assumption, considering motivational variables as antecedents of career exploration helps to understand how students regulate behavior while integrating self and environmental information.

Although career exploration has been widely studied (), fewer studies have addressed its motivational antecedents. Self-Determination Theory (SDT) () presents motivational framework that explores the underlying reasons to get involved in tasks from more controlled or autonomous reasons, which, in turn, suits the purpose of the present study. Based on this theory, observed that more self-determined students exhibited greater autonomy in career exploration. Intrinsic motivation has been consistently linked to adaptive career exploration and career decision-making (). In a sample of 8th grade students, found that those who explore more reported higher levels on most self-determined types of motivation. Both and studies observed positive relationships between intrinsic motivation and self- and environmental exploration. More recently, identify autonomous motivation as a significant predictor of exploration behaviors. Overall, career exploration outcomes may depend on the underlying type of motivation, with more self-determined forms (e.g., intrinsic motivation) likely to produce adaptive career behaviors.

Some studies have linked parental support to career exploration, yet little is known about the processes moderating this relationship (). Intrinsic motivation may enable individuals to self-regulate behavior during exploration. According to , intrinsically motivated individuals exhibit spontaneous curiosity and interest, potentially relying less on external factors. Consequently, individuals’ career exploration may be guided more by enjoyment and values than by parental support. Hence, this study aims to analyze the relationship between parental emotional support and career exploration, considering the moderating effect of intrinsic motivation.

Parental Emotional Support and Career Exploration

Parental support is crucial in adolescents’ career development (; ; ), fostering engagement in career exploration through interaction and shared activities (). Parental emotional support refers to the degree to which parents express encouragement, empathy, affection, and understanding toward their children's academic and career experiences (; ). As a multidimensional construct, encompasses different forms of responsiveness, including affective warmth and empathy and reassurance in times of uncertainty (; ). These nuances may shape how emotional support interacts with individual motivation, clarifying its moderating role in career exploration.

Career exploration is particularly relevant during school transitions, when individuals face new roles and new vocational tasks (; ), and is recognized as a core component in major career models and theories (; ), as it supports career progression throughout lifespan.

While career exploration entails a degree of openness to experience and high levels of self-confidence, parental emotional support can help reduce adolescents’ anxiety and facilitate engagement in career information-seeking (). Indeed, people are more likely to explore careers when they feel emotionally supported by significant others (). Positive associations between parental emotional support and career exploration are well-documented. For instance, found that adolescents explored more when parents were more involved; highlighted the importance of both parents’ and youths’ perception of support, with the latter mediating the relationship between parents' support and career choices; and reported direct effects of parental emotional support on environmental and self-exploration.

These results support the link between parental emotional support and positive career outcomes, emphasizing its importance in engaging adolescents in exploration behaviors. However, parental support effects may not always be linear and uniformly beneficial, as excessive or intrusive involvement can undermine autonomy and exploration (; ).

Intrinsic motivation as a moderator

Intrinsic motivation is the most self-determined form of motivation, occurring when someone engages in a task out of inherent interest and enjoyment (). Individuals with high levels of intrinsic motivation tend to be more persistent, self-driven, and confident (). Intrinsically motivated students are more likely to engage in career development activities for autonomous reasons (; ).

Research has shown that motivation plays a key role in educational and occupational adjustment (; ) and moderates the impact of social cognitive variables (; ). Yet, the moderating role of motivation in the relationship between parental support and career exploration remains underexplored. Although, emotional parental support can provide external encouragement and reduce anxiety during exploration, SDT posits that individuals also require a minimum level of self-determination to fully benefit from such support (). Intrinsic motivation has been associated with greater involvement in self and environmental exploration (; ). Other studies indicate that motivational quality may moderate the impact of contextual factors on adaptive behaviors (; ). However, few studies have examined this moderating mechanism within the career domain, highlighting the importance of testing whether intrinsic motivation buffers or amplifies the effects of parental emotional support on adolescents’ exploration behaviors.

Aligned with SDT, our main argument is that, while parental support fosters career exploration engagement, this effect strength may depend on students’ intrinsic motivation. For instance, showed that students with autonomous motivational profiles benefit more consistently from external resources (as parental support) than those with controlled or amotivated profiles. Therefore, students with high intrinsic motivation may be more receptive to, and better able to act upon parental support, translating it into active career exploration.

Present study

The present work seeks to broaden the knowledge about the role of personal (motivation) and contextual (parental support) factors associated with high school students’ efforts to engage in career exploration. While prior studies have focused on the direct links between parental support and career exploration, less attention has been given to potential moderators or mediators (; ). According to SDT (), parental emotional support may positively influence career exploration behaviors, and this relationship can be moderated by self-regulatory variables such as intrinsic motivation (). Unlike other theories (e.g., Expectancy-Value; Goal-Setting), SDT offers a comprehensive perspective on the regulation of goal-oriented behavior by emphasizing the quality over quantity of motivation. It explains how contexts (e.g., parental support) may nurture the basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness (; ), thereby fostering career exploration internalization (). This framework offers a coherent basis for understanding the motivational mechanisms underlying adolescents’ career development. It is expected that the present findings will contribute to a more nuanced understanding of how individual and contextual support jointly operate in specific career development processes.

In this study we chose to control demographic variables of gender, age, socioeconomic status (SES), and school failure due to their potential impact on career exploration and related vocational factors. Previous research identified gender differences in parent-child relationships () and career-related support (). Although findings on gender impact in career exploration are mixed (), some argue that differences may emerge more clearly in the relationships among vocational variables (). For instance, differences have been found in the relationship between vocational commitment and environmental exploration () and predicting career exploration (). Gender has also been shown to moderate associations between classroom support and career exploration, favoring boys (). Age-related differences have been found in career maturity and career decision-making self-efficacy across time (), intended-systematic exploration (), and self-exploration ().

Regarding the relationship between SES and vocational processes, literature suggests that higher SES tend to relate with the engagement in career exploration activities (). Perceived SES has also been positively associated with career decision certainty (), and has been found to play a moderator role in the relationship between career adaptability and choice satisfaction (), highlighting its potential role in shaping career development pathways.

This study followed a quantitative, cross-sectional correlational design, using a convenience sample of high school students. Based on the literature, we expected to find positive correlations between parental emotional support and career exploration (H1a - environmental exploration; H1b – self-exploration, H1c - intended-systematic exploration, H1d – amount of information) (), as well as positive correlations between intrinsic motivation and career exploration (H2a - environmental exploration, H2b - self-exploration; H2c – intended-systematic exploration, H2d - amount of information) (). Additionally, we anticipated positive correlations between parental emotional support and intrinsic motivation (H3) (). Finally, we expected that intrinsic motivation, as a self-regulatory process, would negatively moderate the relationship between parental emotional support and career exploration (H4a - environmental exploration, H4b – self-exploration; H4c – intended-systematic exploration, H4d - amount of information), resulting in a weaker relationship when intrinsic motivation was higher ().

Method

Participants

The participants were 260 Portuguese high school students from public schools in southern Portugal (54.6% female), aged between 14 and 19 years old (M = 15.92; SD = .99) and within the expected age range for high school students in Portugal. Information regarding previous school failures was collected, with 62.7% reporting that they had never failed any academic year (i.e. not advancing to the next grade due to receiving negative grades in a certain number of subjects). The SES of the participants was determined based on their self-perception and was subsequently categorized into four groups, with the following distribution: 11.9% Low SES, 28.8% Medium SES, 39.2% Medium-High SES, and 20% High SES.

Measures

Parental Emotional Support

We used the Emotional Support subscale from the Career-Related Parent Support Scale (CRPSS) (; adapt. ) to assess career-related emotional support. It intends to assess students' perceptions of parental support concerning career development. This subscale comprises 6 items rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 - strongly disagree; 5 - strongly agree). Higher scores indicate stronger perceptions of parental emotional support. In the present study, the emotional support subscale yielded Cronbach’s alpha value of .86, which is aligned with the results obtained in the original version (α = .85) and the Portuguese adaptation (α = .87).

Career Exploration

The Portuguese version of the Career Exploration Survey (CES; ; adapt. ) was used to measure career exploration. This is a multidimensional self-administered scale aimed at assessing beliefs, processes, and reactions to career exploration. In this study we focused on the subset of items referring to the process dimension of career exploration: self-exploration (5 items); environmental exploration (4 items); intended-systematic exploration (2 items), and amount of information (3 items). Participants rated their answers on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 – Little; 5 - A tremendous amount). Cronbach’s alphas values for the Portuguese version ranged from .63 (Intended-systematic exploration) to .83 (Environmental exploration).

Intrinsic Motivation

The Intrinsic Motivation subscale from the Portuguese version of the Career Decision-Making Autonomy Scale (CDMAS; ; adapt. ) was used to assess intrinsic motivation. This subscale is composed of eight items corresponding to activities related to career decision-making (e.g., seeking information on careers, working hard to attain a career goal). For each item, participants indicate the reasons for participating in the activity using a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 - Does not correspond at all; 7 - Corresponds completely). reported Cronbach’s value ranging from .91 to .95. Regarding intrinsic motivation subscale, in this study we obtained a Cronbach´s alpha value of .91, which is aligned with the value reported by (α = .89)

Procedure

The research protocol was approved by the ethics committee from Polytechnic Institute of Portalegre (Ref. SC 2022/ 20821 – IPP) before being presented to schools. Informed consents and permissions were collected. The study included high school students with signed consent from their parents/ guardians, on the day of data collection. No exclusion criteria were applied. To ensure consistency in the administration of instruments, trained co-researchers and psychologists conducted data collection in the classroom. Participants were informed about the general topic of the study, the voluntary nature of participation, and confidentiality of responses. On average, each assessment lasted 30 minutes.

Data analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS version 29.0. Variables were standardized (z-scores) before creating the interaction terms by multiplying them (). Hierarchical moderated regressions were used to test the direct effects of age, gender, SES level, and school failure (Step 1), emotional support and intrinsic motivation (Step 2), and the two-way interaction term between these latter variables (Step 3) on career exploration behaviors. Moderation analyses were conducted using the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Model 1; ), with 5000 bootstrap samples to estimate confidence intervals for the conditional effects and simple slopes. Conditional effects were examined at one standard deviation below and above the mean values and plotted for low versus high levels of intrinsic motivation ().

Results

Table 1 data shows the descriptive statistics, bivariate correlations, and reliability (Cronbach’s alpha). All the variables were positively and significantly correlated with each other, except for the association between emotional support and amount of information.

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotional support | 3.54 | .92 | (.86) | . | . | |||

| 2. Intrinsic motivation | 4.68 | 1.36 | 16** | (.91) | . | |||

| 3. Environmental exp. | 2.79 | .99 | 22** | .20** | (.79) | |||

| 4. Self-exploration | 3.20 | .86 | .29** | 22** | .37** | (.71) | ||

| 5. Intended-systematic exp. | 2.53 | .96 | .19** | .16* | .49** | .29** | (.67) | |

| 6. Amount of information | 3.17 | .83 | .07 | .13* | .49** | .23** | .42** | (.74) |

There was no indication of multicollinearity issues among the independent and moderator variables, as the Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) values were all less than 10, and the Tolerance values were greater than .10 (). Table 2 presents the results of the hierarchical moderated regressions. The variables in the study explained approximately 13% of the variance in environmental exploration, 15% in self-exploration, 9% in intended-systematic exploration, and 8% in the amount of information.

| Environmental Exploration | Self-Exploration | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | F | R2 | ΔR2 | β | F | R2 | ΔR2 | |

| Step 1 | .52 | .01 | 1.52 | .02 | ||||

| Age | .07 | .03 | ||||||

| GD | -.01 | .06 | ||||||

| SF | -.03 | -.11 | ||||||

| SES | -.03 | .07 | ||||||

| Step 2 | 4.11** | .09 | .08** | 6.57** | .14 | .11** | ||

| ES | .23** | .27** | ||||||

| IM | .13* | .15** | ||||||

| Step 3 | 5.45** | .13 | .04** | 6.16** | .15 | .01 | ||

| ES x IM | -.20** | -.11 | ||||||

| Intended-Systematic Exploration | Amount of Information | |||||||

| β | F | β | F | β | F | β | F | |

| Step 1 | 1.20 | .02 | 3.20 | .05 | ||||

| Age | .03 | .14 | ||||||

| GD | -.13* | -.14** | ||||||

| SF | .03 | -.04 | ||||||

| SES | -.10 | .12* | ||||||

| Step 2 | 3.72** | .08 | .06** | 3.34** | .07 | .03* | ||

| ES | .19** | .07 | ||||||

| IM | .13** | .12 | ||||||

| Step 3 | 3.34** | .09 | .00 | 3.14** | .08 | .01 | ||

| ES x IM | -.07 | -.09 | ||||||

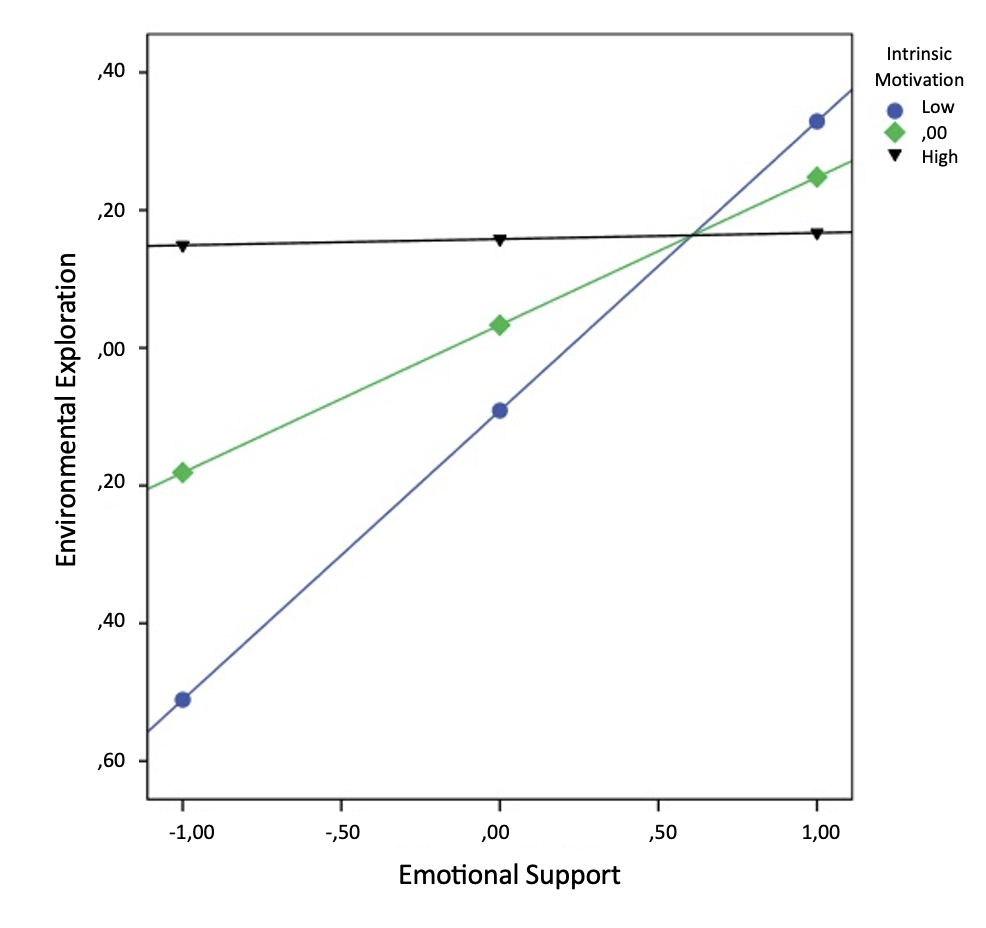

Concerning the sociodemographic variables (Step 1), gender was a significant predictor of intended-systematic exploration (β = -.13; p < .05) and amount of information (β = -.14; p < .05). Additionally, SES was a significant predictor of the amount of information (β = .12; p < .05). In Step 2, emotional support and intrinsic motivation positively predicted environmental exploration (β = .23; p < .05; β = .13; p < .05, respectively), self-exploration (β = .27; p < .01; β = .15; p < .01, respectively), and intended-systematic exploration (β = .19; p < .01; β = .13; p < .01, respectively). Table 2 also shows a significant negative effect of the interaction term (the product of the variables used in Step 2) on environmental exploration (β = -.21; p < .01). Finally, we assessed the moderation effect of intrinsic motivation and plotted the effects of high versus low values. The slopes in Figure 1 suggest that emotional support has a more positive effect on students with low intrinsic motivation (b = .42; p < .01), than on those with high intrinsic motivation (b = .01; p = .91). This indicates those with high levels of intrinsic motivation are not significantly affected by parental emotional support. Conversely, the interaction was not significant when the dependent variables were self-exploration (β = -.11; p = .07), intended-systematic exploration (β = -.07; p = .22), and amount of information (β = -.21; p < .01), suggesting that intrinsic motivation does not have a moderating effect on the relationship between emotional support and these career behaviors.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to analyze the relationship between parental emotional support and career exploration behaviors, considering the moderating effect of intrinsic motivation. Correlational analysis showed that parental emotional support was positively and significantly associated with environmental exploration, self-exploration, and intended-systematic exploration, confirming H1a, H1b and H1c. These findings align with the assumptions of relational perspectives on career exploration (; ), which highlight the importance of significant relationships in adolescents' career development. Empirical evidence (; ) indicates that the security provided by parental emotional support fosters career exploration.

It is worth noting that intended–systematic exploration showed moderate internal consistency (α = .67), which is common in scales with few items, as Cronbach’s alpha is sensitive to this particularity (). However, this does not necessarily indicate low reliability but rather call for a cautious interpretation of the results related to this dimension. In this case, the two items showed positive and moderate correlation (r = .51, p < .01), supporting their internal coherence and the adequacy of the measure in capturing this dimension of career exploration.

Although our results indicate a positive association between parental emotional support and career exploration, this relationship may not be strictly linear. Excessive or controlling involvement can undermine adolescents’ autonomy, suggesting that future studies should examine possible ambivalent or curvilinear effects of parental support. Furthermore, amount of information was not significantly correlated with parental emotional support, so H1d was not confirmed. This may suggest that parental emotional support (item 22: “My parents talk to me when I am worried about my future career”) primarily involves providing encouragement, understanding, and empathy toward self- and environmental exploration. Future research with diversified samples is needed to clarify whether this pattern persists.

Results revealed positive relationships between intrinsic motivation and exploration behaviors, allowing us to confirm H2a, H2b, H2c and H2d. These findings align with previous research (; ; ), linking greater exploratory engagement to students who are more self-driven, autonomous and self-determined in career-related tasks.

Bivariate correlations confirmed H3, as parental emotional support positively correlates with intrinsic motivation. This relationship corroborates the importance of proximal context support in nurturing basic psychological needs (see also ), thereby contributing to higher self-determination in career processes (; ). Consistent with SDT, alongside autonomy and competence, relatedness plays an important role sustaining intrinsic motivation (). Thus, adolescents who perceive greater parental emotional support may also report higher intrinsic motivation and engagement in environmental and self-exploration.

Concerning regression analysis, the explained variance in self-, environmental, and intended-systematic exploration, as well as in amount of information was modest, consistent with other studies examining the antecedents of career exploration (; ; ; ). This underlines the need to expand existing models by incorporating motivational variables (; ).

These results reinforce the idea that career exploration is a multidimensional construct (), encompassing internal and external efforts to engage with future career paths. In this study, environmental, self-, and intended-systematic exploration were consistently associated to parental emotional support and intrinsic motivation, whereas the amount of information showed weaker links. This suggests that experiential or reflective facets of exploration (e.g., exploring career-related environments) are more sensitive to motivational and contextual resources than purely informational outcomes. These results align with prior work (; ), emphasizing the role of volition and environmental support in shaping exploratory behavior.

Although gender differences in career exploration remain inconsistent (), our results showed that females engaged less in intended-systematic exploration and information gathering. At first glance, this contrasts with Lazarides et al.’s (), who reported higher self-exploration among girls. However, this apparent discrepancy may reflect differences across dimensions of career exploration. While self-exploration involves internal reflection, systematic exploration requires active information seeking and planning. In contexts where vocational information remains strongly gender-segregated, girls may perceive fewer viable options (e.g., exclusion from high-prestige and high-income occupational pathways) and, consequently, invest less in information-gathering activities. This interpretation aligns with the notion that exposure to stereotyped environments can constrain the perceived utility of exploration efforts. To reach a deeper understanding on this issue, future research should: 1) analyze different dimensions of career exploration, beyond behaviors (e.g., beliefs and reactions), and 2) examine gender-based differences in the patterns of relationship among other variables of interest ().

Finally, we found that higher socioeconomic status (SES) predicts greater levels of information gathering. Consistent with prior research, SES is linked to improved access to career resources and opportunities, which facilitates more extensive exploration (). Individuals with higher SES may also devote more attention to exploring a wider range of career options, identifying paths that align with personal and professional aspirations ().

As expected, parental emotional support and intrinsic motivation positively predicted self-, environmental, and intended-systematic exploration (; ). However, neither variable yielded significant results predicting amount of information. This may be explained by other dimensions of support not included in this study, such as career modeling or instrumental support, or even more controlled types of motivation (e.g., identified regulation). Therefore, consistent with Paixão and Gamboa (; ), future research should include additional dimensions of parental support and different types of motivation.

Regression analysis also suggests that intrinsic motivation negatively moderates the relationship between parental emotional support and environmental exploration (confirming H4a). No moderating effect was found for the relationship between parental emotional support and the other exploration behaviors, meaning we cannot confirm this hypothesis to self-exploration (H4b), intended-systematic exploration (H4c), and amount of information (H4d). The absence of a moderating effects can be happening because these behaviors may rely greatly on enduring personal traits and self-regulatory competences, as well as internalized motivational processes (; ), making them less sensitive to external support. In contrast, environmental exploration requires more outward engagement, where parental emotional encouragement may play a more prominent compensatory role for students with lower levels of intrinsic motivation. A deeper analysis of the slopes indicates that the influence of parental emotional support is more pronounced among students who are less self-driven, less persistent, and have a weaker sense of autonomy and competence in career exploration. These results support our initial suggestion that a certain level of self-determination may be a necessary condition to achieve adaptive career outcomes.

Implications

This study makes a dual contribution. First, it reinforces the predictive capacity of a specific dimension of career-related parental support. Second, it expands the assumption that the quality of an individual's motivation matters in vocational development. Indeed, it contributes to career exploration literature by showing that the relationship between contextual support and exploration is not linear. Instead, a set of conditions appears to play a crucial role in achieving adaptive career outcomes. One possible explanation for these findings is that individuals who are more self-determined in their career development tasks tend to engage in exploratory activities with greater autonomy, which may reduce their responsiveness to external factors, such as parental emotional support (; ). Within the SDT framework (), these findings highlight that parental emotional support is crucial in encouraging children to engage in exploration activities, especially among those with lower intrinsic motivation.

Several implications for career intervention emerge from our result: (1) differential practices within the career intervention should be adopted, considering students’ motivational functioning in relation to exploration thoughts and behaviors; (2) interventions such as parent education and career counselling should jointly address motivational and vocational processes; (3) promoting career-related parental support to enhance exploration behaviors, particularly for students with low levels of intrinsic motivation. According to , providing support that satisfies basic psychological needs while engaging in exploration tasks may facilitate the internalization process. This highlights the instrumental value of career exploration in improving motivation quality, by increasing autonomy and intrinsic motivation in career development processes, while reducing dependence on contextual support.

Limitations and future research

Future research on this topic should consider not only adolescents’ perceptions of parental emotional support but also parents’ reports. This seems promising as new sources of support and career information emerge during adolescence and shift in relevance over time. Second, the same hypotheses should be tested using adolescents' perceptions of each parent support, since evidence suggests that fathers and mothers may play different roles in influencing career development.

Although sociodemographic variables were controlled, other contextual variables, such as school characteristics, teacher support, or economic context, were not considered and could affect the results. Future studies should address these factors to enhance ecological validity of the model. Additionally, SES was based on students’ self-reports, reflecting subjective perceptions rather than objective family indicators.

As parental support is conceptualized as a multidimensional construct, the model could incorporate other dimensions (e.g., instrumental support, career modeling), especially when considering the moderating effect intrinsic motivation. Moreover, this study focused exclusively on parental emotional support, not considering other relevant sources of support such as peers, teachers, or mentors. In the future, a broader approach can be used to compare the relative influence of these agents.

Finally, given the cross-sectional design adopted, we recommend employing longitudinal designs to better capture the potential interactions between parental emotional support and adolescents’ career exploration. This would clarify the extent to which parental support influences children's career behaviors, and, conversely, the extent to which children’s exploratory behavior influences the levels of emotional support provided by parents.

References

1

2

BARTLEY, Denise; & ROBITSCHEK, Christine (2000). Career exploration: A multivariate analysis of predictors. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 56(1), 63–81. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1999.1708

3

BLUSTEIN, David (1997). A context-rich perspective of career exploration across the life roles. Career Developmental Quarterly, 45(3), 260–274. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.1997.tb00470.x

4

BLUSTEIN, David (2011). A relational theory of working. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.10.004

5

6

CHEN, Shi; CHEN, Huaruo; LING, Hairong; & GU, Xueying (2021). How do students become good workers? Investigating the impact of gender and school on the relationship between career decision-making self-efficacy and career exploration. Sustainability, 13(14), Article 7876. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147876

7

CREED, Peter; FALLON, Tracy; & HOOD, Michelle (2009). The relationship between career adaptability, person and situation variables, and career concerns in young adults. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74(2), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2008.12.004

8

DECI, Edward; & RYAN, Richard (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1104_01

9

DIETRICH, Julia; KRACKE, Bärbel; & NURMI, Jari-Erik (2011). Parents role in adolescents’ decision on a college major: A weekly diary study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(1), 134–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.12.003

10

11

FLUM, Hanoch (2015). Relationships and career development: An integrative approach. In Paul Hartung; Mark Savickas; & Walter Walsh (Eds.), APA Handbook of Career Intervention (Vol. 1, pp. 145–158). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14438-009

12

FLUM, Hanoch; & BLUSTEIN, David (2000). Reinvigorating the study of vocational exploration: Framework for research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 56(3), 380–404. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2000.1721

13

FURMAN, Wyndol; & BUHRMESTER, Duane (1992). Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child development, 63(1), 103-115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb03599.x

14

GAMBOA, Vítor; PAIXÃO, Maria; & JESUS, Saúl (2014). Vocational profiles and internship quality among Portuguese vet students. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 14(2), 221–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-014-9268-0

15

GAMBOA, Vítor; PAIXÃO, Olímpio; & RODRIGUES, Suzi (2021). Validação da Career-Related Parent Support Scale numa amostra de estudantes portugueses. Psychologica, 64(1), 121–140. https://doi.org/10.14195/1647-8606_64-1_6

16

GAMBOA, Vítor; RODRIGUES, Suzi; BÉRTOLO, Filipa; MARCELO, Beatriz; & PAIXÃO, Olímpio (2023). Curiosity saved the cat: Socio-emotional skills mediate the relationship between parental support and career exploration. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, Article 1195534. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1195534

17

GATI, Itamar; & KULCSÁR, Viktória (2021). Making better career decisions: From challenges to opportunities. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 126. Article 103545 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2021.103545

18

GINEVRA, Maria; NOTA, Laura; & FERRARI, Lea (2015). Parental support in adolescents' career development: Parents' and children's perceptions. Career Development Quarterly 63(1), 2–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2015.00091.x

19

20

GUAY, Frédéric (2005). Motivations underlying career decision-making activities: The career decision-making autonomy scale (CDMAS). Journal of Career Assessment, 13(1), 77-97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072704270297

21

GUAY, Frédéric; SENÉCAL, Caroline; GAUTHIER, Lysanne; & FERNET, Claude (2003). Predicting career indecision: A self-determination theory perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50(2), 165–177. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.50.2.165

22

HARDIN, Erin; VARGHESE, Femina; TRAN, Uyen; & CARLSON, Aaron (2006). Anxiety and career exploration: Gender differences in the role of self-construal. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69(2), 346–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2006.05.002

23

HARTUNG, Paul; PORFELI, Erik; & VONDRACEK, Fred (2005). Child vocational development: A review and reconsideration. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66(3), 385–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2004.05.006

24

25

HIRSCHI, Andreas (2018). The fourth industrial revolution: Issues and implications for career research and practice. The Career Development Quarterly, 66(3), 192–204. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12142

26

JIANG, Zhou; NEWMAN, Alexander; LE, Huong; PRESBITERO, Alfred; & ZHENG, Connie (2019). Career exploration: A review and future research agenda. Journal of Vocational Behavior,110, 338–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.08.008

27

28

KATZ, Benjamim; JAEGGI, Susanne; BUSCHKUEHL, Martin; STEGMAN, Alyse; & SHAH, Priti (2014). Differential effect of motivational features on training improvements in school-based cognitive training. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, Article 00242. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00242

29

30

KETTERSON, Timothy; & BLUSTEIN, David (1997). Attachment relationships and the career exploration process. The Career Development Quarterly, 46(2), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.1997.tb01003.x

31

KLEINE, Anne-Kathrin; SCHMITT, Antje; & WISSE, Barbara (2021). Students’ career exploration: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 131, Article 103645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2021.103645

32

33

LAZARIDES, Rebecca; ROHOWSKI, Susanne; OHLEMANN, Svenja; & ITTEL, Angela (2015). The role of classroom characteristics for students’ motivation and career exploration. Educational Psychology, 36(5), 992–1008. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2015.1093608

34

LENT, Robert; & BROWN, Steven (2013). Social cognitive model of career self-management: Toward a unifying view of adaptive career behavior across the life span. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(4), 557–568. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033446

35

LENT, Robert; & BROWN, Steven (2020). Career decision making, fast and slow: Toward an integrative model of intervention for sustainable career choice. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 120, Article 103448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103448

36

LENT, Robert; EZEOFOR, Ijeoma; MORRISON, Ashley; PENN, Lee; & IRELAND, Glenn (2016). Applying the social cognitive model of career self-management to career exploration and decision-making. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 93, 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.12.007

37

LI, Mengting; FAN, Weiqiao; & ZHANG, Li-Fang (2023). Career adaptability and career choice satisfaction: Roles of career self-efficacy and socioeconomic status. The Career Development Quarterly, 71(4), 300–314. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12334

38

MAFTEI, Alexandra; MĂIREAN, Cornelia; & DĂNILĂ, Oana (2023). What can I be when I grow up? Parental support and career exploration among teenagers: The moderating role of dispositional optimism. Personality and Individual Differences, 200, Article 111870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.111870

39

MAO, Ching-Hua (2017). Paternal and maternal support and Taiwanese college students’ indecision: Gender differences. Australian Journal of Career Development, 26(3), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/1038416217725768

40

MARCINKO, Ivana (2015). The moderating role of autonomous motivation on the relationship between subjective well-being and physical health. PLOS ONE, 10(5), Article 0126399. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0126399

41

MONTEIRO, Sílvia; SEABRA, Filipa; SANTOS, Sandra; ALMEIDA, Leandro; & ALMEIDA, Ana (2025). Career intervention effectiveness and motivation: Blended and distance modalities comparison. Revista de Estudios e Investigación en Psicología y Educación, 12(1), Article 11118. https://doi.org/10.17979/reipe.2025.12.1.11118

42

OTIS, Nancy; GROUZET, Frederick; & PELLETIER, Luc (2005). Latent motivational change in an academic setting: A 3-year longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(2), 170–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.97.2.170

43

PAIXÃO, Olímpio; & GAMBOA, Vítor (2017). Motivational profiles and career decision making of high school students. The Career Development Quarterly, 65(3), 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12093

44

PAIXÃO, Olímpio; & GAMBOA, Vítor (2021). Autonomous versus controlled motivation on career indecision: The mediating effect of career exploration. Journal of Career Development, 49(4), 802–815. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845321992544

45

PORFELI, Erik; & LEE, Bora (2012). Career development during childhood and adolescence. New directions for youth development, 2012(134), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.20011

46

RATELLE, Catherine; GUAY, Frederic; VALLERAND, Robert; LAROSE, Simon; & SENÉCAL, Caroline (2007). Autonomous, controlled, and amotivated types of academic motivation: A person-oriented analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(4), 734–746. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.4.734

47

RYAN, Richard; & DECI, Edward (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary educational psychology, 25(1), 54-67. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

48

RYAN, Richard; & DECI, Edward (2019). Brick by brick: The origins, development, and future of self-determination theory. Advances in Motivation Science, 6, 111-156. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.adms.2019.01.001

49

SAKA, Noa; & GATI, Itamar (2007). Applying decision theory to facilitating adolescent career choices. In Vladimir Skorikov; & Wendy Patton (Eds.), Career development in childhood and adolescence (pp. 181-202). Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789460911392_012

50

51

52

STUMPF, Stephen; COLARELLI, Stephen; & HARTMAN, Karen (1983). Development of the career exploration survey (CES). Journal of Vocational Behavior, 22(2), 191–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(83)90028-3

53

54

THOMPSON, Mindi; & SUBICH, Linda (2006). The relation of social status to the career decision-making process. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69(2), 289–301. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2006.04.008

55

TURAN, Erkan; ÇELIK, Eyüp; & TURAN, Mehmet (2014). Perceived social support as predictors of adolescents’ career exploration. Australian Journal of Career Development, 23(3), 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/1038416214535109

56

TURNER, Sherri; ALLIMAN-BRISSETT, Annette; LAPAN, Richard; UDIPI, Sharanya; & ERGUN, Damla (2003). The career-related parent support scale. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 36(2), 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2003.12069084

57

YOUNG, Richard; VALACH, Ladislav; BALL, Jessica; PASELUIKHO, Michele; WONG, Yuk; DEVRIES, Raymond; MCLEAN, Holly; & TURKEL, Hayley (2001). Career development in adolescence as a family project. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 48(2), 190–202. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.48.2.190