Introduction

One of the most promising technological advancements is artificial intelligence (AI). AI has emerged as a powerful force with the revolutionary potential to transform the learning paradigm (). AI can be used to develop adaptive learning systems that are capable of tailoring educational content to meet the needs and learning styles of each student (Gligorea et al., 2023). AI-supported adaptive learning allows the educational system to adjust the material according to the individual needs of the learner (). Through the analysis of learning data, AI can identify students' strengths and weaknesses (), allowing the provision of appropriate learning recommendations and personalised feedback ().

Research on AI in education has gained significant attention in the past decade. A meta-analysis by highlighted the rapid growth of AI, underscoring the urgent need to understand how educators can effectively leverage AI techniques to support students' academic success. This body of research explores various AI-related topics and methodologies, including the Internet of Things, swarm intelligence, deep learning, and neuroscience, as well as assessing the impact of AI on education. However, it is crucial to consider factors such as the age and readiness of learners when designing AI-driven learning environments or fostering collaboration between students and AI systems (). Furthermore, the increasing accessibility of generative AI tools has significantly influenced education, transforming school systems in various ways (). AI has the capacity to process large-scale data quickly and perform in-depth analysis, providing the opportunity to make accurate data-driven decisions (). Today, AI can also support teachers' instruction (), enabling them to focus on creative aspects and develop students' unique characteristics (), while administrative tasks can be automated (). This creates an environment where teachers can interact more closely with students, build stronger relationships, and provide more intensive guidance.

Although the implementation of AI in education is progressing rapidly, it still faces significant challenges (). A lack of in-depth understanding of the full potential of AI (), coupled with insufficient participation in it integration into curricula (), can hinder progress. Furthermore, infrastructure gaps and limited technological resources in some educational institutions can reduce the effectiveness of AI implementation ().

An often overlooked aspect in developing AI-based educational solutions is the recognition that each individual has a unique learning style (). Therefore, this study focusses on optimising AI to provide personalised responses and support to the individual needs of students. Creating an adaptive and motivating learning environment is the key to improving participation and learning outcomes. The aims of this study was to investigate how students use AI in the learning process and to examine its influence on their motivation and participation. By outlining how this technology can be optimised to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of teaching and learning, this research hopes to offer practical insights to policymakers, educational institutions, and practitioners in the field. Hence, we formulate the research questions.

Theoretical framework

Personalized learning

The core concept of personalized learning theory is that each individual learns in a unique way (). In recent years, personalized learning has gained recognition as an effective instructional approach for accommodating the diverse needs of students (). This educational approach emphasises student individuality, designing learning experiences that align with each learner’s needs, interests, and pace (; ). Central to this theory is the teacher’s understanding of students’ individual characteristics, including learning styles (), comprehension levels (), and personal preferences (), in order to tailor appropriate learning experiences. Moreover, personalised learning encourages the provision of choice and flexibility throughout the teaching and learning process, supporting students in engaging with content in ways that best suit their abilities and motivations (; ).

AI in education

AI is a broad field focused on automated decision making without requiring human intervention (). AI has revolutionised the education sector by improving personalised learning, automating administrative tasks, and improving student engagement (). AI-powered adaptive learning systems analyse student data to customise educational content based on individual learning styles, strengths, and weaknesses, thus promoting a more effective learning experience (). These systems use machine learning algorithms to identify patterns in student performance and provide real-time feedback, allowing educators to intervene when necessary. Additionally, AI-driven chatbots and virtual tutors offer on-demand support, helping students reinforce their understanding outside the classroom (). AI in education can create more inclusive and accessible learning for diverse students.

Despite its advantages, AI in education also presents challenges related to data privacy, ethical considerations, and the digital divide (). Adopting human-machine collaboration theory emphasises the importance of cooperation between teachers and artificial intelligence (). Human-machine collaboration theory is an approach that considers how humans and machine processors can work together synergistically to achieve more optimal outcomes than they could independently (). This theory is relevant in today’s era of technological advancement, where artificial processors, automation, and robotics are increasingly influential. Its core principles, educational applications, challenges, and impacts across sectors remain crucial areas of discussion.

Constructivism and motivation in learning

Constructivism is a learning theory that emphasises the active role of learners in building their own understanding and knowledge through experience and interaction with their environment (). According to this perspective, learning is not a passive process of receiving information, but an active process in which students build their knowledge based on prior experiences and social interactions and encompasses cognitive, social, moral, and other areas of development (). Vygotsky’s concept Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) highlights the importance of scaffolding, where learners receive guidance from teachers or peers to bridge the gap between their current knowledge and their potential understanding (). In a constructivist learning environment, students engage in problem solving, critical thinking, and collaborative activities that foster deeper comprehension and long-term knowledge retention ().

Motivation plays a crucial role in constructivist learning, as it drives students to engage in meaningful learning experiences and persist in the face of challenges (). Self-determination theory (SDT) suggests that intrinsic motivation, driven by autonomy, competence, and relatedness, is essential for effective learning (). When learners perceive that they have control over their learning process and can relate new information to their existing knowledge, they are more likely to remain motivated and engaged (). Constructivist approaches that incorporate student-centred learning, project-based tasks, and real-world applications enhance motivation by making learning more relevant and personally meaningful (). Constructivist learning fosters autonomy and collaboration, boosting intrinsic motivation and lifelong learning.

Method

Participants

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of XXX, ensuring compliance with institutional ethical standards. A total of 1,294 students (51.16% female and 48.84% male) were selected in Indonesia using a random sampling technique from March to July 2024. The participants had a mean age of 14.56 years (SD = 3.59). This cross-sectional study included only students who provided informed consent prior to participation. Table 1 presents the detailed demographic characteristics of the sample.

Instruments

The instruments comprised two components: AI usage and motivation to use AI. The students completed the online survey. On average, the survey took approximately 10-20 minutes to complete, including time to provide instructions and clarifying questions.

The use of AI in the learning process

This instruments was to measuring students' frequency of AI usage and perceptions of AI's effectiveness in assisting them with academic tasks. These instrument was adapted from and modified by authors. Comprising five items, respondents rate their anxiety using a 4-point Likert scale, varying from 1 (indicating never) to 4 (representing very often). The initial items exhibited strong reliability, boasting a Cronbach's alpha of .91. Open-ended questions are 3 to capture additional insights from respondents develop by authors based on theoretical framework as we mentioned earlier. The survey covered topics such as the types of AI tools they used, the tasks they completed with AI, and their main reasons for using AI.

Motivation use of AI

The motivation to use AI in the learning process questionnaire was adopted from and consisted of four items. Examples of these items include: “The ability to effectively use AI is important to me”, “Learning and implementing innovations in artificial AI are a priority for me”, “It is important for me to stay updated on developments related to AI”, and “I attach great importance to strengthening my skills in using artificial AI.” The original items were validated, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .92, composite reliability (CR) of .92, and an average variance extracted (AVE) of .75. Motivation was measured using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Meanwhile, participation refers to students’ active engagement in classroom activities, measured by the frequency of their contributions.

Data analysis

This study began with an initial data analysis using descriptive statistics, including the mean (M) and standard deviation (SD), along with correlation assessments between variables, conducted using SPSS version 29. To examine changes in students’ motivation before and after using AI, paired-samples t-tests were subsequently performed across educational levels. Effect sizes were also calculated to assess the magnitude of these changes. Additionally, R software was utilized to generate visual representations of the descriptive variables, illustrating students’ response patterns and highlighting trends in motivation and participation.

Results

The use of AI in the learning process

As illustrated in Table 2, participants generally used AI technologies during their learning processes, with mean scores ranging from 1.33 to 2.71. In particular, students expressed the greatest confidence in the utility of AI for academic tasks, as indicated by the statement 'In your opinion, how helpful is AI in completing assignments?' which received the highest mean score of 2.71 (SD = 1.03). On the contrary, the statement 'Have you ever received a warning or penalty from a teacher / trainer for using AI in your assignments?' secured the lowest mean score of 1.33 (SD = .64). This suggests that while students generally appreciate the benefits of AI in enhancing their learning experiences, they may lack awareness regarding the potential risks associated with its use, such as academic dishonesty or overreliance on technology.

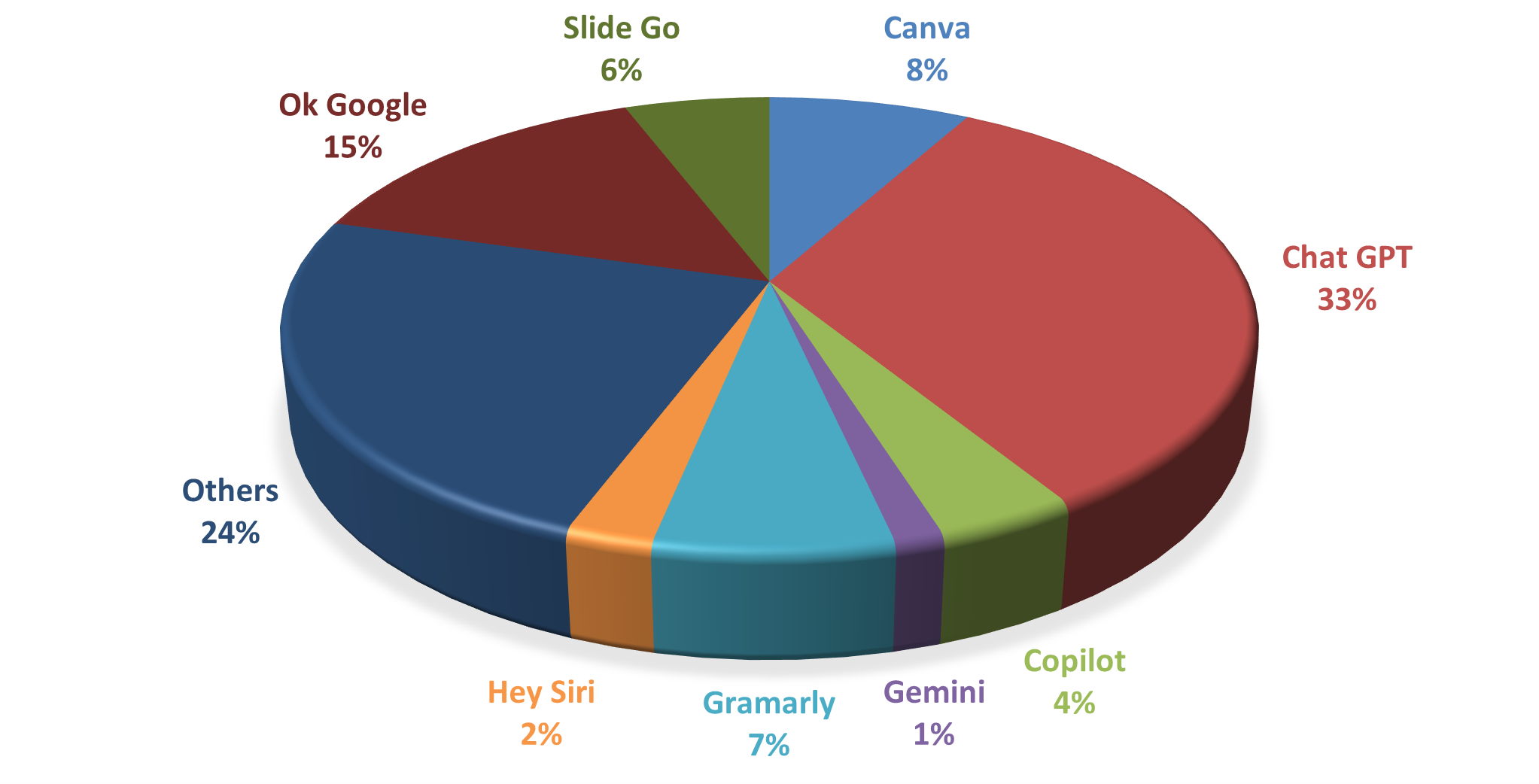

Additionally, we also collected students’ responses to the open-ended question: ‘What type of AI do you use most often?”.

Figure 1 presented the types of AI commonly used by participants, along with their corresponding percentages. The highest percentage was for ChatGPT, with 33% of the respondents indicating its use, reflecting students’ strong reliance on AI tools that support writing and communication tasks. In contrast, the lowest percentage was for Gemini, with only 1% of participants reporting its use, suggesting limited awareness or low perceived relevance for academic purposes. Canva accounted for 8%, indicating students’ preference for visual design tools that enhance presentation quality, while SlideGo, at 6%, pointed to its utility in creating structured academic presentations. Ok Google had 15%, reflecting its role as a quick information-seeking and problem-solving tool, whereas Grammarly, at 7%, highlighted its perceived usefulness for improving language accuracy in academic writing. This distribution reflected the varying functionalities and user familiarity with different AI tools in the learning process.

Furthermore, the results for the question “What types of tasks do you often complete using AI?” indicated the tasks that students most commonly performed, along with the corresponding percentages of respondents. The most frequently reported task was summarizing articles or journal assignments, with 55.10% of participants indicating that they used AI for this purpose. This was closely followed by essay or paper writing at 50.31% and research and information gathering at 49.46%. Text translation and presentation creation were also notable tasks, reported by 30.37% and 30.06% of students, respectively. In contrast, mathematics or statistics assignments were completed less frequently using AI, as indicated by 24.11%, and other tasks accounted for only 3.10% of responses.

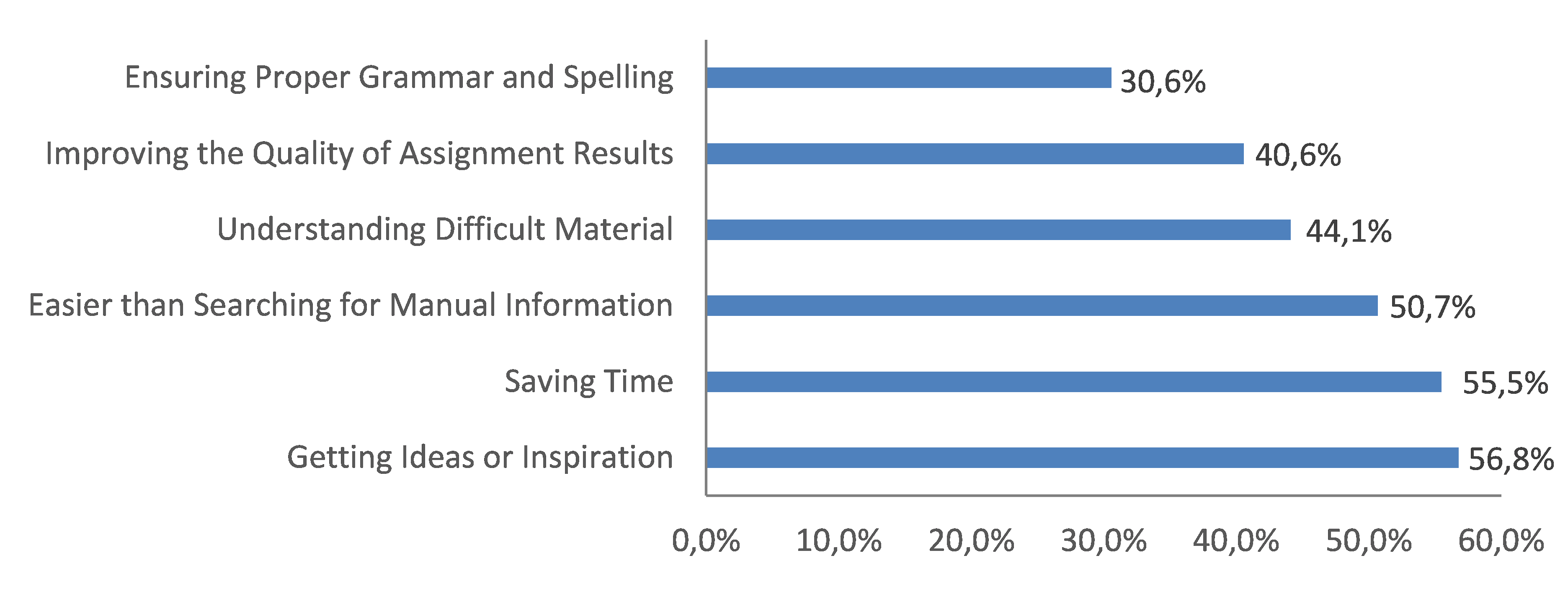

Furthermore, the questions 'What is the main reason for using AI to help with school or college assignments?

Figure 2 shows the main reasons students use AI to help with their school or college assignments, along with the corresponding frequencies and percentages. The most commonly cited reason is "Getting Ideas or Inspiration," with 735 responses (56.80%). In contrast, the least cited reason is "Ensuring Proper Grammar and Spelling," with 396 responses (30.60%). This indicates that while students rely heavily on AI for creative support, they are less concerned with its role in grammar and spelling assistance.

Motivation in the learning process

To determine whether AI influences the learning process and whether its use reflects dependency or optimisation, a quantitative analysis was conducted based on the feedback of the respondents. Dependency was examined by assessing the frequency and types of tasks students relied on AI for, distinguishing between productive use that supported learning and overreliance that indicated potential dependency.

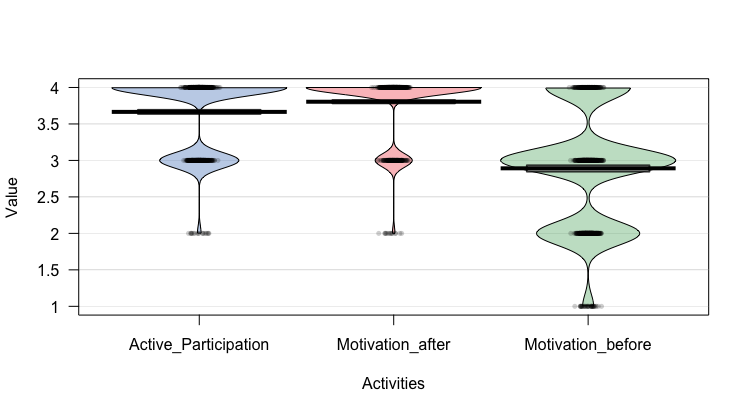

The mean scores indicate an increase in motivation after using AI (M = 4.10, SD = .70) compared to before using AI (M = 2.90, SD = .80). Furthermore, active participation shows a relatively high mean score (M = 3.80, SD = 0.60). In terms of data normality, suggested that skewness values should not exceed |3|, and kurtosis should remain below |10|. For this study, the skewness values ranged between -.54 and -.16, while kurtosis was observed between -.33 and .92. Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances was not significant for higher education, F(2, 386) = .39, p = .674, primary school, F(2, 255) = 2.29, p = .104, and secondary school, F(2, 644) = 1.86, p = .156, indicating that the assumption of homogeneity of variances was met.

Additionally, the correlation analysis reveals a positive relationship between motivation before and after using AI (r = .21) and a stronger correlation between motivation after using AI and active participation (r = .69), suggesting that the use of AI may contribute to greater participation in learning activities. To strengthen the conclusions drawn from the descriptive analysis, a difference test was conducted to compare the motivation of the students before and after using AI in learning process. In more detail, the descriptive statistics for motivation and active participation are illustrated in Figure 3.

The paired-sample t-tests in Table 3 indicated that motivation scores increased significantly following the use of AI across all educational levels. For example, in higher education, motivation rose from M = 2.86 (SD = .78) before AI use to M = 3.82 (SD = .43) after, with a large effect size (Cohen’s d = .91). Similar significant increases were observed in secondary and primary education, suggesting a substantial improvement in motivation following AI use.

Discussion

The findings indicate that AI has become an integral part of student academic activities, with a notable emphasis on its perceived usefulness in completing assignments. The relatively high mean score for AI’s help suggests that students recognise its potential to enhance efficiency and improve academic performance (). These findings align with previous research highlighting the growing reliance on AI in education and its perceived advantages in streamlining learning processes (; ; ). Studies have shown that AI tools can improve student engagement and productivity (; ), yet there remains a need for greater awareness of ethical considerations and responsible usage. This showed the importance of developing clear guidelines and instructional strategies to ensure that AI is used as a complementary tool rather than a substitute for critical thinking and independent learning.

Our results show that among the AI tools surveyed, ChatGPT had the highest usage and recognition among students, while tools such as Gemini were rarely used or known. This pattern supports the claim that students prefer applications offering immediate, practical benefits—such as writing assistance and content creation—aligning with prior research (; ; ) and highlighting the growing importance of effective communication tools for academic success. Additionally, the results indicate that Canva was among the most frequently used AI tools by students, alongside ChatGPT. While the study did not specifically measure the reasons for this preference, the high usage suggests that students are more inclined to adopt tools they find accessible or helpful for completing tasks. This finding highlights the potential value of providing guidance and training on various AI tools to support a more effective learning environment (; ).

The results on the types of tasks that students frequently complete using AI reveal clear trends in their academic preferences and needs. The predominant use of AI for summarizing articles or journal assignments indicates that students are seeking efficient ways to digest complex information, suggesting an emphasis on comprehension and retention in their learning processes (). This aligns with previous research highlighting the increasing reliance on AI to improve understanding and reduce cognitive load in academic tasks (; ). The high usage rates for essay writing and research further underscore the pivotal role that AI plays in helping students produce well-informed and structured work. Tasks such as text translation and presentation creation are also commonly performed using AI, whereas its reported use for mathematics or statistics assignments is comparatively lower. Although the study did not differentiate between specific fields of study, this pattern may suggest that students perceive certain subjects as requiring more traditional learning methods or additional guidance (), or that they encounter challenges in effectively applying AI tools in quantitative contexts (). Further research is needed to explore how subject-specific differences influence AI adoption and usage in academic tasks.

In addition to the types of tasks, the reasons for using AI reveal deeper insights into student motivations. The overwhelming preference for AI as a source of inspiration suggests a shift toward using technology as a creative aid rather than merely a tool for technical assistance (). This observation aligns with existing literature emphasizing the importance of creativity in education (; ; ), as students increasingly turn to AI for idea generation and enhancing their academic expression. These findings indicate that students value AI not only for efficiency but also for supporting creativity in their learning processes. However, this interpretation is based on self-reported data and broad patterns; further research is needed to confirm these trends, particularly across different subjects and contexts, which is addressed in the limitations and directions for future research.

In terms of the main reasons for using AI to support school or college assignments, the most commonly cited reason is “getting ideas or inspiration,” which may reflect students’ increasing reliance on technology to enhance creativity and generate new perspectives in their work (). In contrast, the least cited reason is “ensuring proper grammar and spelling,” suggesting that students perceive technical corrections as less critical or readily manageable through other means (). This pattern indicates that while students heavily rely on AI for creative and cognitive support, they are comparatively less concerned with its role in basic technical assistance. By utilising tools such as creativity interactive AI visualisations, AI further supports the comprehension of complex materials, simplifies difficult concepts, and strengthens students’ overall learning processes (). This can foster greater motivation and participation in the learning process (; ).

This study demonstrates that the integration of AI in education significantly increases student motivation. Before AI implementation, student motivation tended to be low, but improved after AI was incorporated into the learning process. AI facilitates more interactive and personalised learning experiences, incorporating gamification elements that foster intrinsic motivation ().

This study demonstrates that the integration of AI in education significantly increases student motivation. Before AI implementation, student motivation tended to be low, but improved after AI was incorporated into the learning process. This improvement suggests that AI tools can offer tailored support, enhance engagement, and make learning experiences more interactive and relevant to students’ interests. Such findings align with previous research highlighting the potential of AI to foster motivation and active participation in educational settings (). Additionally, AI allows students to engage in self-directed learning, regulate their own learning pace, and develop a sense of responsibility for their educational progress. Students reported increased active participation, indicating that they engaged more in interactive tasks aligned with their interests, promoting full participation in the learning process, and influence of motivation on the process and results activities (). Therefore, motivation to learn supports better academic performance and knowledge acquisition ().

This research has several limitations that should be acknowledged. The study relied on self-reported data collected through an online questionnaire, which may be influenced by participants’ subjective biases and does not necessarily reflect actual behaviors in the learning process. Additionally, the open-ended research instrument was not formally validated within this sample, which may limit the reliability and generalizability of the results. The absence of a control group prevents causal conclusions between AI use, motivation, and participation, so the observed associations should be interpreted with caution. Contextual factors specific to the educational and cultural setting in Indonesia, such as variations in digital literacy, access to AI tools, and institutional support, may have influenced students’ responses and the patterns observed. For future research, longitudinal designs are recommended to examine changes in motivation and participation over time, along with validated instruments and control or comparison groups to better assess AI’s effects. Studies in diverse educational and cultural contexts, as well as mixed-methods approaches, could provide deeper insights into how AI interacts with student motivation, engagement, and learning outcomes.

Conclusions

The findings of this study indicate a significant integration of AI technologies into the learning process, reflecting both the utility and potential challenges associated with their use. Participants generally recognised the benefits of AI in improving academic tasks, particularly in summarising articles, writing essays, and conducting research. The results suggest that students are primarily motivated to use AI tools for creative support, such as generating ideas, rather than for technical assistance, such as grammar checks. Variability in the usage of AI tools, with a preference for applications that enhance writing and visual presentations, suggests that students tend to prioritise tools that align with their immediate academic needs. This pattern underscores the potential value of providing guidance and training on the broader range of AI functionalities available for learning, helping students utilise AI more effectively and responsibly in diverse academic contexts.

Furthermore, the analysis of motivation and participation reveals that AI not only boosts student motivation but also positively correlates with their active participation in learning activities. The data show a marked increase in motivation after the use of AI, indicating its effectiveness in promoting a more interactive and engaging educational environment. These results highlight the importance of integrating AI technologies into curricula to enhance student participation and motivation. The implications of the study suggest that educators should focus on developing strategies that use AI tools to promote creativity and active learning while addressing the potential downsides of the use of technology in education. This research also contributes to the growing body of evidence supporting the incorporation of AI in educational settings, advocating for a balanced approach that maximises benefits while mitigating risks.

Limitation and future research

Although this study provides valuable information on the use of AI in the learning process, it also has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the study relies on self-reported data, which may be subject to biases such as social desirability and recall bias, potentially affecting the accuracy of the responses. Additionally, the research was conducted within a specific cultural and educational context in Indonesia, which may limit the generalisability of the findings to other regions or educational systems. Furthermore, the cross-sectional design does not allow causal inferences to be drawn about the relationship between AI use and changes in motivation and participation, highlighting the need for longitudinal studies to better understand these dynamics over time. Future research should aim to address these limitations by employing mixed methods that combine quantitative surveys with qualitative interviews to gain deeper insights into students' experiences with AI. Expanding the participant pool to include various educational institutions and cultural backgrounds would enhance the generalisability of the findings. Additionally, longitudinal studies could explore the long-term effects of AI usage on learning outcomes, motivation, and participation, providing a more complete understanding of how AI tools can be optimally integrated into educational practices. Finally, further investigation into the potential risks associated with AI use, such as academic dishonesty and over-reliance on technology, would be crucial to developing guidelines and best practices for educators and students alike.

References

1

AFZAAL, Muhammad; ZIA, Aayesha; NOURI, Jalal; & FORS, Uno (2024). Informative feedback and explainable AI-based recommendations to support students’ self-regulation. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 29(1), 331-354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-023-09650-0

2

ALAQLOBI, Obied; ALDUAIS, Ahmed; QASEM, Fawaz; & ALASMARI, Muhammad (2024). A SWOT analysis of generative AI in applied linguistics: Leveraging strengths, addressing weaknesses, seizing opportunities, and mitigating threats. F1000Research, 13, Article 1040. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.155378.1

3

ALI, Sajid; ABUHMED, Tamer; EL-SAPPAGH, Shaker; MUHAMMAD, Khan; ALONSO-MORAL, Jose M; CONFALONIERI, Roberto; GUIDOTTI, Riccardo; DEL SER, Javier; DÍAZ-RODRÍGUEZ, Natalia; & HERRERA, Francisco (2023). Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): What we know and what is left to attain Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence. Information Fusion, 99, Article 101805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2023.101805

4

ALLIL, Kamaal (2024). Integrating AI-driven marketing analytics techniques into the classroom: Pedagogical strategies for enhancing student engagement and future business success. Journal of Marketing Analytics, 12, 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41270-023-00281-z

5

ALUKO, Henry Adeyemi; ALUKO, Ayodele; OFFIAH, Goodness Amaka; OGUNJIMI, Funke; ALUKO, Akinseye Olatokunbo; ALALADE, Funmi Margareth; OGEZE UKEJE, Ikechukwu; & NWANI, Chinyere Happiness (2025). Exploring the effectiveness of AI-generated learning materials in facilitating active learning strategies and knowledge retention in higher education. International Journal of Organizational Analysis. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-07-2024-4632

6

ANANTRASIRICHAI, Nantheera, & BULL, David (2022). Artificial intelligence in the creative industries: A review. Artificial Intelligence Review, 55(1), 589–656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-021-10039-7

7

8

BAJAJ, Richa; & SHARMA, Vidushi (2018). Smart education with artificial intelligence based determination of learning styles. Procedia Computer Science, 132, 834-842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2018.05.095

9

BEN-ASSULI, Ofir; HEART, Tsipi; KLEMPFNER Robert; & PADMAN, Rema (2023). Human-machine collaboration for feature selection and integration to improve congestive heart failure risk prediction. Decision Support Systems, 172, Article 113982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2023.113982

10

BERNACKI, Matthew L.; GREENE, Meghan J; & LOBCZOWSKI, Nikki G. (2021). A systematic review of research on personalized learning: Personalized by whom, to what, how, and for what purpose (s)? Educational Psychology Review, 33(4), 1675-1715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09615-8

11

12

BOUSSIOUX, Léonard; LANE, Jacqueline N.; ZHANG, Miaomiao; JACIMOVIC Vladimir; & LAKHANI, Karim R. (2024). The Crowdless Future? Generative AI and creative problem-solving. Organization Science, 35(5), 1589-1607. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2023.18430

14

BRUSILOVSKY, Peter (2024). AI in education, learner control, and human-AI collaboration. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 34(1), 122-135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-023-00356-z

15

CHAI, Ching Sing; YU, Ding; KING, Ronnel B; & ZHOU, Ying (2024). Development and validation of the artificial intelligence learning intention scale (AILIS) for university students. Sage Open, 14(2), 21582440241242188. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440241242188

16

CHAI, Fangyuan; MA, Jiajia; WANG, Yi; ZHU, Jun; & HAN, Tingting (2024). Grading by AI makes me feel fairer? How different evaluators affect college students’ perception of fairness. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1221177. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1221177

17

CHAN, Cecilia Ka Yuk (2023). A comprehensive AI policy education framework for university teaching and learning. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), Article 38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00408-3

18

CHIU, Thomas K. F. (2024). The impact of Generative AI (GenAI) on practices, policies and research direction in education: A case of ChatGPT and Midjourney. Interactive Learning Environments, 32(10), 6187-6203. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2023.2253861

19

CLEGG, Stewart; & SARKER, Soumodip (2024). Artificial intelligence and management education: A conceptualization of human-machine interaction. The International Journal of Management Education, 22(3), Article 101007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2024.101007

20

DAVAR, Narius Farhad; DEWAN, M. Ali Akber; & ZHANG, Xiaokun (2025). AI chatbots in education: Challenges and opportunities. Information, 16(3), Article 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16030235

21

DEBS, Luciana; MILLER, Kurtis D.; ASHBY, Iryna; & EXTER, Marisa (2019). Students’ perspectives on different teaching methods: Comparing innovative and traditional courses in a technology program. Research in Science & Technological Education, 37(3), 297-323. https://doi.org/10.1080/02635143.2018.1551199

22

DECI, Edward L; & RYAN, Richard M. (2012). Self-Determination Theory. In Paul A. M. Van Lange, Arie W. Kruglanski & E. Tory Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology: Volume 1 (pp. 416-437). SAGE https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446249215.n21

23

DEMINK-CARTHEW, Jessica; NETCOH, Steven; & FARBER, Katy (2020). Exploring the potential for students to develop self-awareness through personalized learning. The Journal of Educational Research, 113(3), 165-176. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2020.1764467

24

DIEKER, Lisa A.; HINES, Rebecca; WILKINS, Ilene; HUGHES, Charles; SCOTT, Karyn Hawkins; SMITH, Shaunn; INGRAHAM, Kathleen; ALI, Kamran; ZAUGG, Tiffanie; & SHAH, Sachin (2024). Using an artificial intelligence (AI) agent to support teacher instruction and student learning. Journal of Special Education Preparation, 4(2), 78-88. https://doi.org/10.33043/d8xb94q7

25

DOĞAN, Miray; CELIK, Arda; & ARSLAN, Hasan (2025). AI In higher education: Risks and opportunities from the academician perspective. European Journal of Education, 60(1), Article e12863. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12863

26

DOS SANTOS, Giselle Glória Balbino; SOARES, Adriana Benevides; & MONTEIRO, Marcia (2022). Habilidades sociais, motivação para o aprendizado e clima escolar no ensino fundamental e médio. Revista de Estudios e Investigación en Psicología y Educación, 9(2), 301-317. https://doi.org/10.17979/reipe.2022.9.2.9208

27

EDEN, Chima Abimbola; CHISOM, Onyebuchi Nneamaka; & ADENIYI, Idowu Sulaimon (2024). Integrating AI in education: Opportunities, challenges, and ethical considerations. Magna Scientia Advanced Research and Reviews, 10(2), 006-013. https://doi.org/10.30574/msarr.2024.10.2.0039

28

ESCALANTE, Juan; PACK, Austin; BARRETT, Alex (2023). AI-generated feedback on writing: Insights into efficacy and ENL student preference. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), Article 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00425-2

29

FANG, Menglin; ABDALLAH, Asma Khaleel; & VORFOLOMEYEVA, Olga (2024). Collaborative AI-enhanced digital mind-mapping as a tool for stimulating creative thinking in inclusive education for students with neurodevelopmental disorders. BMC Psychology, 12(1), Article 488. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01975-4

30

FARIDA, Farida; ALAMSYAH, Yosep Aspat; & SUHERMAN, Suherman (2023). Assessment in educational context: The case of environmental literacy, digital literacy, and its relation to mathematical thinking skill. Revista de Educación a Distancia (RED), 23(76), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.6018/red.552231

31

FATOUROS, Cherryl (1995). Young children using computers: Planning appropriate learning experiences. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 20(2), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1177/183693919502000202

32

GERLICH, Michael (2025). AI tools in society: Impacts on cognitive offloading and the future of critical thinking. Societies, 15(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15010006

33

HABIB, Sabrina; VOGEL, Thomas; & THORNE, Evelyn (2025). Student perspectives on creative pedagogy: Considerations for the Age of AI. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 56, Article 101767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2025.101767

34

JONASSEN, David H; & ROHRER-MURPHY, Lucia (1999). Activity theory as a framework for designing constructivist learning environments. Educational Technology Research and Development, 47(1), 61-79. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02299477

35

KHALIFA, Mohamed; & ALBADAWY, Mona (2024). Using artificial intelligence in academic writing and research: An essential productivity tool. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine Update, 5, Article 100145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpbup.2024.100145

36

37

KUZMINSKA, Olena; POHREBNIAK, Denys; MAZORCHUK, Mariia; & OSADCHYI, Viacheslav (2024). Leveraging AI tools for enhancing project team dynamics: Impact on self-efficacy and student engagement. Information Technologies and Learning Tools, 100(2), 92-109. https://doi.org/10.33407/itlt.v100i2.5602

38

LIU, Liu (2025). Impact of AI gamification on EFL learning outcomes and nonlinear dynamic motivation: Comparing adaptive learning paths, conversational agents, and storytelling. Education and Information Technologies, 30, 11299-11338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-13296-5

39

MILLS, Carol J. (2003). Characteristics of effective teachers of gifted students: Teacher background and personality styles of students. Gifted Child Quarterly, 47(4), 272-281. https://doi.org/10.1177/001698620304700404

40

MONTEIRO, Sílvia; SEABRA, Filipa; SANTOS, Sandra; ALMEIDA, Leandro S.; & DE ALMEIDA, Ana Tomás (2025). Career intervention effectiveness and motivation: Blended and distance modalities comparison. Revista de Estudios e Investigación en Psicología y Educación, 12(1), Article e11118. https://doi.org/10.17979/reipe.2025.12.1.11118

41

MUTAMBIK, Ibrahim (2024). The use of AI-driven automation to enhance student learning experiences in the KSA: An alternative pathway to sustainable education. Sustainability, 16(14), Article 5970. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16145970

42

OAKHILL, Jane; HARTT, Joanne; & SAMOLS, Deborah (2005). Levels of comprehension monitoring and working memory in good and poor comprehenders. Reading and Writing, 18, 657-686. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-005-3355-z

43

OWOC, Mieczysław Lech; SAWICKA, Agnieszka; & WEICHBROTH, Paweł (2019). Artificial intelligence technologies in education: Benefits, challenges and strategies of implementation. In Mieczysław Lech Owoc & Maciej Pondel (eds), Artificial intelligence for knowledge management. AI4KM 2019. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, Vol. 599 (pp. 37-58). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85001-2_4

44

PANE, John F.; STEINER, Elizabeth D.; BAIRD, Matthew D; & HAMILTON, Laura S. (2015). Continued Progress: Promising evidence on personalized learning. Rand Corporation. https://doi.org/10.7249/RR1365

45

PEDRO, Francesc; SUBOSA, Miguel; RIVAS, Axel; & VALVERDE, Paula (2019). Artificial intelligence in education: Challenges and opportunities for sustainable development. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12799/6533

46

RODWAY, Paul; & SCHEPMAN, Astrid (2023). The impact of adopting AI educational technologies on projected course satisfaction in university students. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 5, Article 100150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2023.100150

47

ROMANELLI, Frank; BIRD, Eleanora; & RYAN, Melody (2009). Learning styles: A review of theory, application, and best practices. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 73(1). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2690881/

48

SAJJA, Ramteja; SERMET, Yusuf; CIKMAZ, Muhammed; CWIERTNY, David; & DEMIR, Ibrahim (2024). Artificial intelligence-enabled intelligent assistant for personalized and adaptive learning in higher education. Information, 15(10), Article 596. https://doi.org/10.3390/info15100596

49

SCHUMANN, Christian-Andreas; SCHWILL, Emelie; MROTZEK, Isabell; BAHN, Lydia; & BAHN, Thomas (2024). An AI-supported adaptive study system for individualized university services. In David Guralnick, Michael E. Auer, & Antonella Poce (Eds.) Creative Approaches to Technology-Enhanced Learning for the Workplace and Higher Education. TLIC 2024. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, Vol. 1166 (pp 168-175). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-73427-4_17

50

51

SHEMSHACK, Atikah; KINSHUK, kinshuk; & SPECTOR, Jonathan Michael (2021). A comprehensive analysis of personalized learning components. Journal of Computers in Education, 8(4), 485-503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-021-00188-7

52

SHOAIB, Muhammad; SAYED, Nasir; SINGH, Jaiteg; SHAFI, Jana; KHAN, Shakir; & ALI, Farman (2024). AI student success predictor: Enhancing personalized learning in campus management systems. Computers in Human Behavior, 158, Article 108301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2024.108301

53

SØRENSEN, Natasha Lee; BEMMAN, Brian; JENSEN, Martin Bach; MOESLUND, Thomas B; & THOMSEN, Janus Laust (2023). Machine learning in general practice: Scoping review of administrative task support and automation. BMC Primary Care, 24(1), Article 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-023-01969-y

54

SU, C‐H.; & CHENG, C‐H. (2015). A mobile gamification learning system for improving the learning motivation and achievements. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 31(3), 268-286. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12088

55

SUHERMAN, Suherman; & VIDÁKOVICH, Tibor (2024). Role of creative self-efficacy and perceived creativity as predictors of mathematical creative thinking: Mediating role of computational thinking. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 53, 101591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2024.101591

56

SUPRIADI, Nanang; JAMALUDDIN Z, Wan; & SUHERMAN, Suherman (2024). The role of learning anxiety and mathematical reasoning as predictor of promoting learning motivation: The mediating role of mathematical problem solving. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 52, Article 101497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2024.101497

57

TAPALOVA, Olga; & ZHIYENBAYEVA, Nadezhda (2022). Artificial intelligence in education: AIEd for personalised learning pathways. Electronic Journal of E-Learning, 20(5), 639-653. https://doi.org/10.34190/ejel.20.5.2597

58

UPPAL, Komal; & HAJIAN, Shiva (2024). Students’ perceptions of ChatGPT in higher education: A study of academic enhancement, procrastination, and ethical concerns. European Journal of Educational Research, 14(1), 199-211. https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.14.1.199

59

VOLKMAR, Gioia; FISCHER, Peter M; & REINECKE, Sven (2022). Artificial intelligence and machine learning: Exploring drivers, barriers, and future developments in marketing management. Journal of Business Research, 149, 599-614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.04.007

60

61

62

WANNER, Thomas; & PALMER, Edward (2015). Personalising learning: Exploring student and teacher perceptions about flexible learning and assessment in a flipped university course. Computers & Education, 88, 354-369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.07.008

63

WIDIARTI, Yenni (2024). Canva and comic strips: Facilitate on teaching writing instruction. International Journal of Contemporary Studies in Education (IJ-CSE), 3(3), 245-255. https://doi.org/10.56855/ijcse.v3i3.1170

64

WINGSTRÖM, Roosa; HAUTALA, Johanna; & LUNDMAN, Riina (2024). Redefining creativity in the era of AI? Perspectives of computer scientists and new media artists. Creativity Research Journal, 36(2), 177-193. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2022.2107850

65

XXU, Yongjun; LIU, Xin; CAO, Xin; HUANG, Changping; LIU, Enke; QIAN, Sen; LIU, Xingchen; WU, Yanjun; DONG, Fengliang; QIU, Cheng-Wei; QIU, Junjun; HUA, Keqin; SU, Wentao; WU, Jian; XU, Huiyu; HAN, Yong; FU, Chenguang; YIN, Zhigang; LIU, Miao; … & ZHANG, Jiabao (2021). Artificial intelligence: A powerful paradigm for scientific research. The Innovation, 2(4), Article 100179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100179

66

YUAN, Lingjie; & LIU, Xiaojuan (2025). The effect of artificial intelligence tools on EFL learners’ engagement, enjoyment, and motivation. Computers in Human Behavior, 162, Article 108474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2024.108474

67

YURT, Eyup; & KASARCI, Ismail (2024). A questionnaire of artificial intelligence use motives: A contribution to investigating the connection between AI and motivation. International Journal of Technology in Education, 7(2), 308-325. https://doi.org/10.46328/ijte.725

68

ZAWACKI-RICHTER, Olaf; MARÍN, Victoria I.; BOND, Melissa; & GOUVERNEUR, Franziska (2019). Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education - where are the educators? International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 16(1), Article 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-019-0171-0

69

ZHAI, Xuesong; CHU, Xiaoyan; CHAI, Ching Sing; JONG, Morris Siu Yung; ISTENIC, Andreja; SPECTOR, Michael; LIU, Jia-Bao; YUAN, Jing; & LI, Yan (2021). A review of artificial intelligence (AI) in education from 2010 to 2020. Complexity, 2021(1), Article 8812542. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8812542

70

ZHOU, Wei (2023). Chat GPT integrated with voice assistant as learning oral chat-based constructive communication to improve communicative competence for EFL earners (No. arXiv:2311.00718). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2311.00718